Decision Tree Examples: 5 Worked Models for Business Strategy

Decision tree examples with worked probabilities and expected values for make-vs-buy, market entry, product launch, pricing, and hiring strategy decisions.

Decision tree examples show up constantly in strategy work -- Harvard Business Review has featured them as a core analytical method since the 1960s -- but most online versions skip the part that matters: assigning real probabilities and calculating expected values that actually inform a recommendation.

A decision tree is only as useful as the numbers on its branches. Without probabilities and payoffs, it is just a flowchart with extra shapes. With them, it becomes a quantitative framework that turns ambiguous strategic choices into defensible, data-backed recommendations.

After building decision trees across 80+ strategy, due diligence, and investment committee engagements, we have found that five business scenarios account for roughly 70% of all decision tree use cases in consulting. This guide walks through each one with worked examples, shows how to assign probabilities and compute expected values, compares decision trees to issue trees and logic trees, and covers how to build them in PowerPoint. For the broader framework context, see our Strategic Frameworks Guide.

What Is a Decision Tree?#

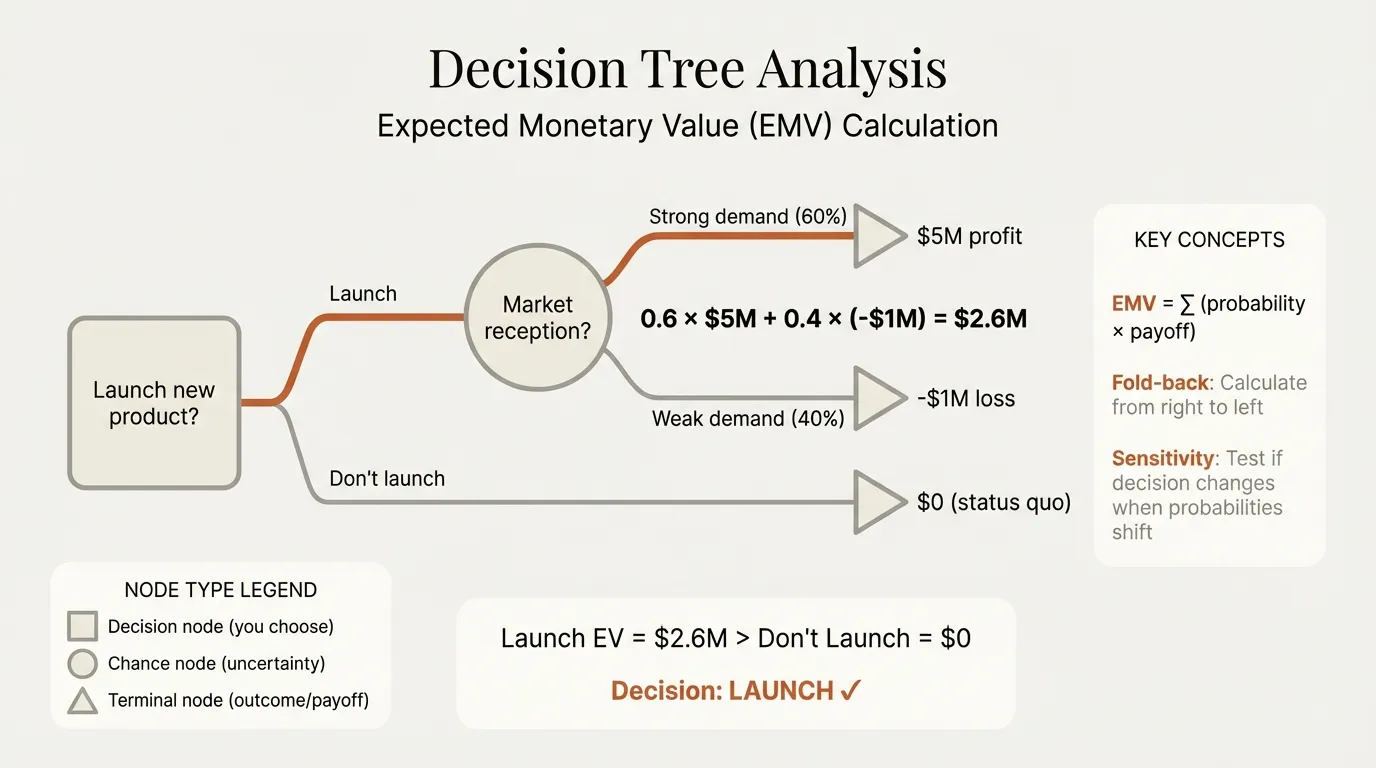

A decision tree is a branching diagram that maps sequential decisions, uncertain events, and their outcomes to evaluate options under uncertainty. It consists of three types of nodes:

| Node Type | Symbol | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision node | Square | A choice the decision-maker controls | Build in-house vs. outsource |

| Chance node | Circle | An uncertain event with multiple outcomes | Market demand is high, medium, or low |

| Terminal node | Triangle | The final payoff or outcome | $4.2M net profit over 3 years |

The tree reads left to right. To find the optimal path, you work backward ("fold back") -- multiplying payoffs by probabilities at chance nodes and selecting the highest expected value (EV) at decision nodes.

EV at a chance node = (Probability_1 x Payoff_1) + (Probability_2 x Payoff_2) + ... + (Probability_n x Payoff_n)

At each decision node, choose the branch with the highest EV. The result is a quantified recommendation that shows not just what to do, but why the math supports it.

When to Use a Decision Tree#

Decision trees excel when decisions are sequential, outcomes are uncertain but estimable, payoffs can be quantified, and the number of stages is manageable (2-4). They fall short when you are comparing options against multiple weighted criteria simultaneously (use a decision matrix instead), decomposing a problem into root causes (use an issue tree), or modeling so many branches that simulation would be more practical.

5 Decision Tree Examples for Business Strategy#

Example 1: Make-vs-Buy Decision#

Scenario: A mid-market SaaS company must decide whether to build a reporting module in-house or license a third-party solution. The build option costs more upfront but has higher long-term margin if adoption is strong.

Tree structure:

Decision node: Build In-House vs. License Third-Party

Build In-House path:

- Development succeeds on time (P = 0.60) → High adoption (P = 0.50): +$4.2M / Low adoption (P = 0.50): +$1.1M

- Development delayed 6 months (P = 0.30) → High adoption (P = 0.40): +$2.0M / Low adoption (P = 0.60): -$0.5M

- Development fails, pivot to license (P = 0.10): -$1.8M

License Third-Party path:

- Vendor stable, good integration (P = 0.70): +$2.4M

- Vendor raises prices or degrades (P = 0.20): +$0.8M

- Vendor exits market, forced migration (P = 0.10): -$0.6M

Expected value calculation:

Build In-House EV:

- On-time branch: 0.60 x [(0.50 x $4.2M) + (0.50 x $1.1M)] = 0.60 x $2.65M = $1.590M

- Delayed branch: 0.30 x [(0.40 x $2.0M) + (0.60 x -$0.5M)] = 0.30 x $0.50M = $0.150M

- Failure branch: 0.10 x -$1.8M = -$0.180M

- Total Build EV = $1.560M

License Third-Party EV:

- 0.70 x $2.4M + 0.20 x $0.8M + 0.10 x -$0.6M = $1.68M + $0.16M - $0.06M = $1.780M

Recommendation: The license option has a higher expected value ($1.78M vs. $1.56M). The build option has higher upside ($4.2M best case) but also higher downside (-$1.8M worst case). For a company with limited engineering bandwidth, licensing is the risk-adjusted optimal choice. If the team has strong development capacity and can push the on-time probability above 0.70, the build option overtakes licensing.

Example 2: Market Entry Decision#

Scenario: A European consumer goods firm is evaluating entry into the U.S. market. The decision tree models the entry mode (acquisition vs. organic) and subsequent demand scenarios.

Tree structure:

Decision node: Acquire U.S. Brand vs. Organic Entry

Acquire path (upfront cost: $45M):

- Integration succeeds (P = 0.55) → Strong demand (P = 0.60): +$38M / Moderate demand (P = 0.40): +$14M

- Integration struggles (P = 0.45) → Strong demand (P = 0.40): +$8M / Moderate demand (P = 0.60): -$12M

Organic Entry path (upfront cost: $15M):

- Brand gains traction (P = 0.35) → Strong demand (P = 0.65): +$22M / Moderate demand (P = 0.35): +$9M

- Brand struggles (P = 0.65) → Pivot to niche (P = 0.50): +$2M / Exit market (P = 0.50): -$10M

Expected value calculation:

Acquire EV:

- Integration success: 0.55 x [(0.60 x $38M) + (0.40 x $14M)] = 0.55 x $28.4M = $15.62M

- Integration struggles: 0.45 x [(0.40 x $8M) + (0.60 x -$12M)] = 0.45 x -$4.0M = -$1.80M

- Total Acquire EV = $13.82M

Organic EV:

- Traction: 0.35 x [(0.65 x $22M) + (0.35 x $9M)] = 0.35 x $17.45M = $6.11M

- Struggles: 0.65 x [(0.50 x $2M) + (0.50 x -$10M)] = 0.65 x -$4.0M = -$2.60M

- Total Organic EV = $3.51M

Recommendation: Acquisition has a significantly higher expected value ($13.82M vs. $3.51M) despite the larger upfront investment. The key assumption driving this result is integration success probability. If due diligence reveals cultural or operational risks that push integration success below 0.35, the acquisition EV drops below organic. Sensitivity analysis on this single variable should be the focus of the investment committee discussion.

Example 3: Product Launch Go/No-Go#

Scenario: A pharmaceutical company deciding whether to proceed with a Phase III clinical trial for a drug that passed Phase II. The decision includes a potential fast-track regulatory path.

Tree structure:

Decision node: Proceed with Phase III vs. Shelve and Reallocate Budget

Proceed path (investment: $120M):

- Trial succeeds (P = 0.45) → Decision: Apply for fast-track vs. Standard review

- Fast-track approved (P = 0.30): +$680M / Fast-track denied, standard path (P = 0.70): +$410M

- Standard review approved (P = 0.85): +$390M / Standard denied (P = 0.15): -$120M

- Trial fails (P = 0.55): -$120M

Shelve path:

- Reallocate to existing pipeline: +$45M (risk-adjusted value of next-best project)

Expected value calculation:

At the fast-track vs. standard decision node (reached only if trial succeeds):

- Fast-track EV: (0.30 x $680M) + (0.70 x $410M) = $204M + $287M = $491M

- Standard EV: (0.85 x $390M) + (0.15 x -$120M) = $331.5M - $18M = $313.5M

- Optimal choice at this node: Fast-track ($491M > $313.5M)

Proceed EV (rolling back):

- Trial succeeds and fast-track: 0.45 x $491M = $220.95M

- Trial fails: 0.55 x -$120M = -$66M

- Total Proceed EV = $154.95M

Shelve EV: $45M

Recommendation: Proceeding with Phase III has an expected value of $154.95M versus $45M for shelving. The decision tree also reveals that if the trial succeeds, the fast-track application is always the optimal sub-decision regardless of approval odds, because the denied-fast-track outcome still leads to standard review. This nested decision insight is something a simple go/no-go analysis would miss entirely.

Example 4: Pricing Strategy Decision#

Scenario: A B2B software company launching a new product tier must choose between premium pricing ($299/user/year) and competitive pricing ($149/user/year). Market response depends on competitor reaction.

Decision node: Premium Pricing vs. Competitive Pricing

Premium path:

- Competitors hold prices (P = 0.40) → High conversion (P = 0.45): +$8.2M / Low conversion (P = 0.55): +$3.1M

- Competitors undercut (P = 0.60) → High retention (P = 0.30): +$4.5M / Low retention (P = 0.70): +$1.2M

Competitive path:

- Competitors hold prices (P = 0.55) → High volume (P = 0.60): +$6.8M / Moderate volume (P = 0.40): +$4.1M

- Competitors engage in price war (P = 0.45) → Win share (P = 0.35): +$3.2M / Margin erosion (P = 0.65): +$0.4M

Result: Premium EV = $3.47M. Competitive EV = $3.77M. Competitive pricing edges ahead, but the gap is narrow. The decision hinges on competitor reaction probabilities -- if market intelligence suggests a price war is unlikely (P below 0.30), competitive pricing becomes clearly dominant. If competitors are aggressive, the premium path preserves margin in the downside scenario ($1.2M worst case vs. $0.4M).

Example 5: Hiring Decision (Senior Leader)#

Scenario: A growth-stage company needs a VP of Sales. The choice is between promoting an internal candidate with deep product knowledge but limited leadership experience versus hiring externally with a strong track record but cultural fit risk.

Decision node: Promote Internal vs. Hire External

Internal promotion (ramp cost: $80K):

- Grows into role (P = 0.50) → Team exceeds quota (P = 0.55): +$2.8M / Team hits quota (P = 0.45): +$1.6M

- Plateaus, needs coaching (P = 0.35) → Coaching succeeds (P = 0.60): +$1.2M / Replace in 12 months (P = 0.40): -$0.4M

- Fails, replaced in 6 months (P = 0.15): -$0.6M

External hire (recruitment + ramp cost: $250K):

- Strong cultural fit (P = 0.45) → Team exceeds quota (P = 0.65): +$3.4M / Team hits quota (P = 0.35): +$1.9M

- Adequate fit, some friction (P = 0.35) → Retains team (P = 0.50): +$1.4M / Loses key reps (P = 0.50): +$0.2M

- Poor fit, departs in 9 months (P = 0.20): -$0.8M

Result: Internal EV = $1.24M. External EV = $1.41M. The external hire has a modestly higher expected value, but the internal candidate carries less downside risk (-$0.6M worst case vs. -$0.8M). If the company has a strong culture that external hires historically struggle with, adjusting the "strong cultural fit" probability from 0.45 to 0.30 reverses the recommendation. This is a case where the decision tree does not give a clear-cut answer -- it shows how sensitive the outcome is to cultural fit assumptions, which is itself a valuable insight for the leadership team.

Continue reading: Agenda Slide PowerPoint · Flowchart in PowerPoint · Pitch Deck Guide

Build consulting slides in seconds

Describe what you need. AI generates structured, polished slides — charts and visuals included.

How to Assign Probabilities and Expected Values#

The hardest part of any decision tree is assigning credible probabilities. Here is the four-step process we use.

Step 1: Anchor on base rates. Find the historical base rate before estimating. M&A integration success rates, clinical trial phase probabilities, product launch conversion benchmarks -- base rates prevent the overconfidence bias that plagues expert estimates.

Step 2: Adjust with specific evidence. Use situation-specific knowledge to adjust up or down. A Phase III trial with strong Phase II data has higher odds than the general base rate. Document the adjustment and reasoning.

Step 3: Ensure probabilities sum to 1.0. At every chance node, branches must add to 100%. If you assign 0.70 to success, you are explicitly asserting 0.30 failure.

Step 4: Stress-test with sensitivity analysis. Identify the 1-2 probabilities that most affect the final EV. If a 10% shift in one probability flips the recommendation, that variable needs more research before deciding.

| Probability Source | Reliability | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Historical company data | High | Past product launch conversion rates |

| Industry reports and studies | Medium-High | Pharmaceutical trial success rates by phase |

| Expert judgment (calibrated) | Medium | Senior team estimates with documented reasoning |

| Gut feel (uncalibrated) | Low | "I think it is about 60%" with no supporting data |

Decision Tree vs. Issue Tree vs. Logic Tree#

These three tree structures serve fundamentally different purposes, and confusing them is one of the most common mistakes in strategy work.

| Dimension | Decision Tree | Issue Tree | Logic Tree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Choose the optimal action under uncertainty | Decompose a problem into root causes | Structure an argument or hypothesis |

| Nodes | Decision nodes (squares) + Chance nodes (circles) | Question/issue branches | Assertion/evidence branches |

| Quantitative? | Yes -- probabilities and expected values | Sometimes -- can include data but often qualitative | Rarely -- focuses on logical structure |

| Direction | Forward (action → outcome) | Downward (problem → sub-problems) | Downward (conclusion → supporting points) |

| Output | A recommended decision with quantified rationale | A MECE decomposition of the problem | A structured argument or hypothesis set |

| When to use | "Which option should we choose?" | "Why is this happening?" or "What are all the factors?" | "How do we structure this argument?" |

How they connect: On a typical engagement, you start with an issue tree to decompose the problem into MECE sub-issues, build decision trees for sub-issues requiring strategic choices, and present the recommendation using a logic tree that follows the Pyramid Principle. For templates, see the issue tree template and root cause analysis template.

Building Decision Tree Examples in PowerPoint#

PowerPoint is not purpose-built for decision trees, but you can create presentation-ready trees with the right approach.

Manual method: Start with a decision node (square) on the left, draw branches using connectors for each option, add chance nodes (circles) where uncertainty exists, label branches with probabilities, and end with terminal nodes showing payoffs. Group the entire tree after completion -- connectors detach when ungrouped shapes move. Limit trees to 3 decision stages per slide to prevent label overlap.

Template method: Tools like Deckary include pre-built decision tree templates with formatted nodes, connectors, and label placeholders. For trees with more than two stages, this saves 30-45 minutes of manual formatting per slide. If building manually, alignment shortcuts keep nodes evenly spaced.

Key Takeaways#

Decision trees are one of the few strategy frameworks that produce a quantified recommendation rather than a qualitative assessment. Their value comes from forcing explicit assumptions about probabilities and payoffs -- assumptions that can be debated, stress-tested, and updated as new information arrives.

Core principles:

- Every branch needs a probability and every terminal node needs a payoff -- without these, a decision tree is just a flowchart

- Work backward from outcomes to decisions -- fold back expected values to find the optimal path

- Sensitivity-test the critical assumptions -- if one probability shift flips the recommendation, that variable needs more data before deciding

- Use decision trees for sequential, uncertain choices -- for multi-criteria evaluations without uncertainty, a decision matrix is the better tool

- Keep trees to 2-3 decision stages per slide -- more than that and the visual becomes unreadable in a presentation setting

For step-by-step guidance on building your own, see our how to make a decision tree guide, or start with the decision tree template for a ready-to-use PowerPoint layout. For the full strategic frameworks toolkit, explore the Strategic Frameworks Guide.

Build consulting slides in seconds

Describe what you need. AI generates structured, polished slides — charts and visuals included.

Try Free