The Pyramid Principle: How Consultants Structure Arguments That Win

How McKinsey consultants use the Pyramid Principle and SCQA framework to structure arguments. Includes MECE logic, action titles, and slide examples.

The Pyramid Principle is the communication framework that defines how consultants at McKinsey, BCG, and Bain structure arguments. Developed by Barbara Minto during her time at McKinsey in the 1960s, it inverts how most people naturally communicate: instead of building to your conclusion, you lead with it.

This approach exists because executives don't have time to follow your analytical journey. They want your destination first, then the supporting logic. A CEO might have fifteen minutes between meetings—if your recommendation is on slide 45, they'll never see it. For a complete guide to applying these principles in MBB-style presentations, see our Consulting Presentations Guide.

What Is the Pyramid Principle?#

The Pyramid Principle is a communication framework developed by Barbara Minto during her time at McKinsey in the 1960s. Minto was the first female MBA hired by the firm—one of only eight women in her Harvard Business School class of 600—and she went on to train generations of McKinsey consultants on structured communication.

Her insight was simple but counterintuitive:

You think from the bottom up, but you present from the top down.

When you analyze a problem, you gather data, run analyses, and gradually build toward a conclusion. That's how thinking works. But that's not how you should communicate.

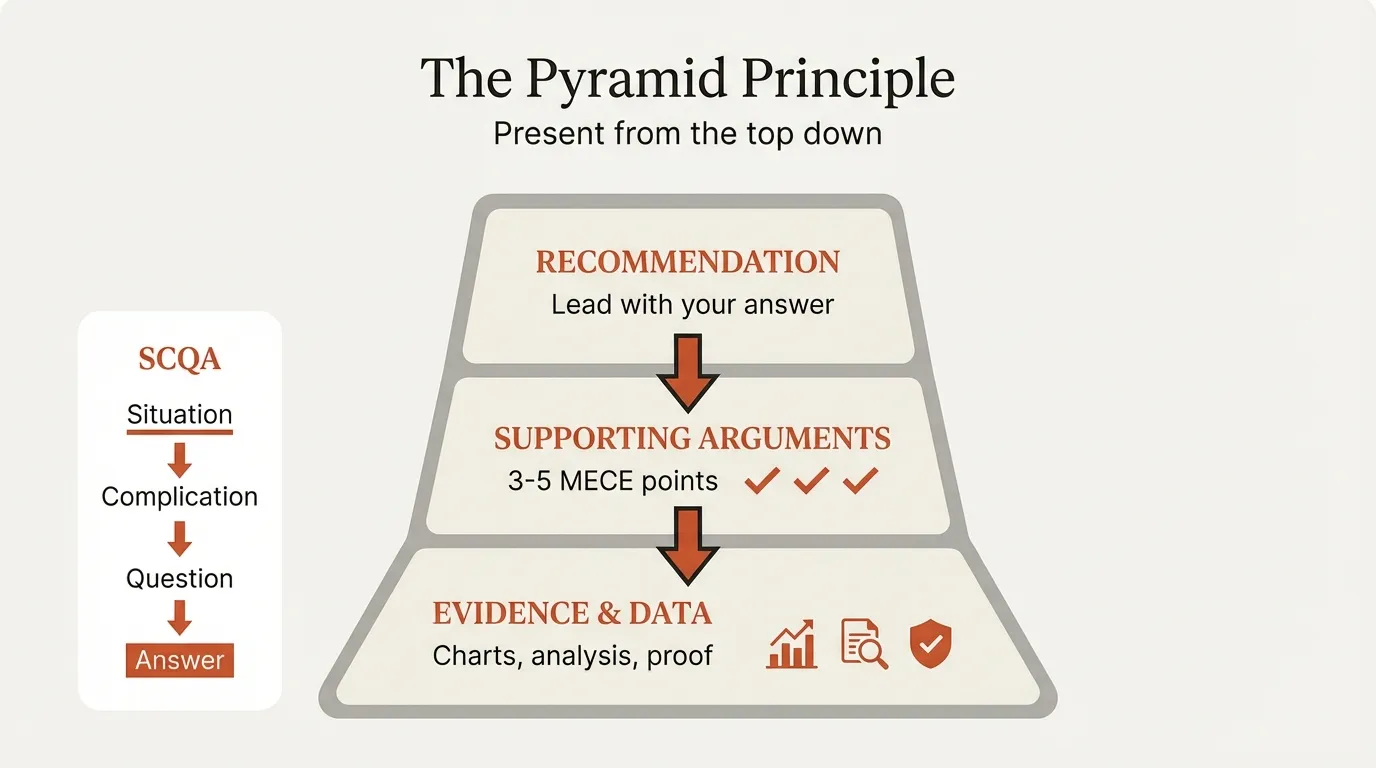

Instead, you flip the pyramid:

| Level | Contains | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Top | Your recommendation | "We should enter the German market" |

| Middle | Supporting arguments | "The market is growing, we have capability, ROI is positive" |

| Bottom | Data and evidence | Market research, capability assessment, financial model |

You lead with the answer. Then you support it.

Why This Matters for Your Audience#

Executives don't want to follow your analytical journey. They want your destination.

Consider how a typical executive's day works:

- Back-to-back meetings

- Hundreds of decisions to make

- Information overload from every direction

When you walk into a room and start with background and context, you're asking them to hold that information in working memory while you slowly build to a point. Research shows people can only hold about four chunks of information in working memory at any given time.

By the time you get to your recommendation, they've forgotten your setup.

The Pyramid Principle respects your audience's time and cognitive load. It says: "Here's what I recommend. Here's why. Here's the evidence. Ask me anything."

That's confidence. That's clarity. That's what gets recommendations approved.

The Three Levels of the Pyramid#

Level 1: The Governing Thought#

This is your main point—the single most important thing you want your audience to remember.

In a strategy presentation, this might be:

- "We recommend acquiring Company X for $50M"

- "The organization should reduce headcount by 15% over 18 months"

- "Digital transformation should focus on three priority areas"

Notice these are specific, actionable statements. Not "We analyzed the market" or "There are several options to consider."

The governing thought should pass what I call the "elevator test": if you only had 30 seconds with the CEO, what would you say?

Level 2: Key Supporting Arguments#

These are the 3-5 main reasons your recommendation is correct. They answer the question "Why?" that your governing thought raises.

For "We recommend acquiring Company X":

- Strategic fit is strong (complements our product portfolio)

- Financial returns are attractive (15% IRR, 3-year payback)

- Integration risk is manageable (similar culture, proven playbook)

Each argument should be:

- A complete thought (not just a topic like "Financials")

- Mutually exclusive from other arguments (no overlap)

- Collectively exhaustive (together they cover the key considerations)

This is where MECE—Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive—comes in. More on that below.

Level 3: Supporting Data and Evidence#

Each Level 2 argument is supported by data, analysis, and examples.

For "Financial returns are attractive":

- DCF analysis shows $80M NPV

- Comparable transactions valued at 6-8x EBITDA; we're paying 5.5x

- Synergy case is conservative; upside from cross-selling not included

This is where your charts, data tables, and detailed analysis live. The work you did to reach your conclusion—but presented in service of the argument, not as a journey through your analytical process.

The SCQA Framework: How to Open Strong#

The Pyramid Principle tells you to lead with your recommendation. But you can't just walk into a room and say "Buy Company X" without context.

That's where SCQA comes in. Developed by Minto as a companion to the Pyramid Principle, SCQA structures the opening of your communication:

Situation: The current state—something your audience already knows and agrees with.

Complication: What changed, what's wrong, or what's at stake.

Question: The question that naturally arises from the complication.

Answer: Your recommendation (the top of your pyramid).

SCQA Example#

Situation: We've grown 20% annually in North America for five years and have strong brand recognition in our core segments.

Complication: North American growth is slowing to 5% as we saturate our core markets. Meanwhile, competitors are expanding into Europe and building positions we'll struggle to challenge later.

Question: How should we sustain growth while competitors move internationally?

Answer: We should enter the German market in Q3, starting with our enterprise segment where we have the strongest differentiation.

Then you support that answer with your pyramid: three arguments, each backed by data.

SCQA works because it mirrors how your audience thinks. They need context, they need to understand why action is required, and they need to know what you're solving for before they can evaluate your answer.

Continue reading: Agile vs Waterfall · Bar Charts in PowerPoint · Investment Banking Pitch Book

Build MBB-quality slides in seconds

Describe what you need. AI generates structured, polished slides — charts and visuals included.

MECE: The Logic Test for Your Arguments#

MECE stands for Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive. Barbara Minto developed this concept alongside the Pyramid Principle, and it's become foundational to consulting thinking.

Mutually Exclusive: Your categories don't overlap. Each supporting argument is distinct.

Collectively Exhaustive: Your categories cover everything. Together, your arguments address all the important considerations.

Why MECE Matters#

Without MECE, your arguments leak credibility:

Not MECE (overlapping):

- "The acquisition makes strategic sense"

- "It will strengthen our competitive position"

- "It aligns with our long-term vision"

These three points are essentially saying the same thing three different ways. Your audience will notice.

MECE:

- "Strategic fit is strong" (capability/portfolio argument)

- "Financial returns are attractive" (value argument)

- "Integration risk is manageable" (execution argument)

These are distinct categories. An executive can evaluate each independently and see that you've covered the key dimensions of the decision.

MECE Example: Diagnosing a Problem#

If you're analyzing why revenue declined, a MECE breakdown might be:

By driver:

- Volume (units sold)

- Price (revenue per unit)

- Mix (shift between high/low margin products)

By segment:

- Enterprise customers

- Mid-market customers

- SMB customers

By geography:

- North America

- Europe

- Asia-Pacific

Each framework is MECE within itself. Pick the one that best fits your analysis.

Applying the Pyramid Principle to Slides#

The Pyramid Principle isn't just for verbal communication. It directly shapes how you structure presentations.

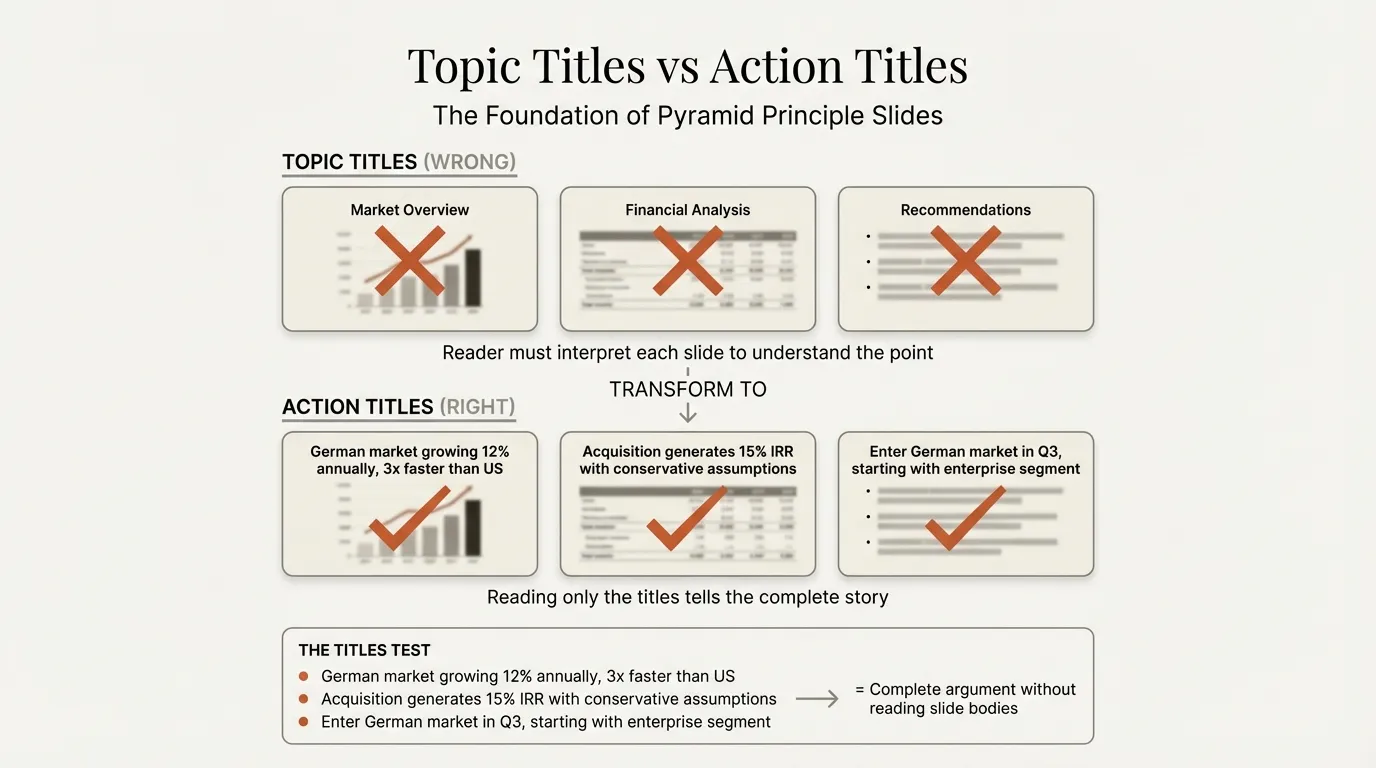

Action Titles#

Every slide should have an action title—a complete sentence that states the slide's main point. The title is the top of that slide's mini-pyramid.

Weak titles (topics, not points):

- "Market Overview"

- "Financial Analysis"

- "Competitor Comparison"

Strong action titles:

- "The German market is growing 12% annually, 3x the rate of North America"

- "Acquisition generates 15% IRR with conservative synergy assumptions"

- "We outperform competitors on 4 of 6 key purchase criteria"

With action titles, an executive can flip through your deck reading only the titles and understand your entire argument. This is called the "titles test" and it's how partners at consulting firms review decks.

One Message Per Slide#

Each slide should make exactly one point. If you find yourself writing "and" in your title, you probably have two slides.

The body of the slide—charts, text, images—exists to support that one point. Everything on the slide should answer the question: "Why should I believe the title?"

Deck Structure#

Your overall deck follows the pyramid:

- Executive summary (1-2 slides): SCQA setup plus key recommendation and supporting arguments

- Section for each supporting argument: One section per Level 2 point

- Appendix: Detailed backup, additional data, methodology

The executive summary should stand alone. A time-pressed executive should be able to read just those slides and understand your recommendation and reasoning.

Common Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)#

Mistake 1: Building Up Instead of Leading Down#

This is the most common error. You start with background, move through analysis, and arrive at a recommendation at the end.

This approach:

- Loses your audience before you get to the point

- Feels like you're defending your work rather than advising on a decision

- Makes it hard for executives to engage because they don't know where you're headed

Fix: Write your recommendation first. Then ask "Why?" to generate your supporting arguments. Then ask "How do I know?" to identify your evidence.

Mistake 2: Topics Instead of Points#

Organizing by topic rather than by argument:

- "Market Analysis"

- "Competitive Landscape"

- "Financial Model"

This tells your audience what you looked at, not what you concluded.

Fix: Convert topics to points:

- "The market is attractive and growing"

- "We can win against current competitors"

- "Returns justify the investment"

Mistake 3: Too Many Supporting Arguments#

More than 5 supporting arguments signals you haven't synthesized your thinking. You're presenting a list, not a structured argument.

Fix: Group related points. If you have 8 arguments, you probably have 3 arguments with sub-points.

Mistake 4: Burying the Real Ask#

Sometimes consultants soften their recommendations by hiding them in passive language or conditional framing.

Weak: "The analysis suggests that there may be an opportunity to consider expanding into new markets."

Strong: "We recommend entering the German market in Q3."

Fix: Write your recommendation as a direct statement. Use active voice. Be specific about what, when, and how.

Mistake 5: Assuming Your Audience's Knowledge#

The curse of knowledge is real. You've spent weeks on this analysis. Your audience is seeing it for the first time.

Fix: Use the Situation in SCQA to establish shared context. Define terms if needed. Don't skip logical steps that seem obvious to you.

Pyramid Principle in Practice: A Full Example#

Let's walk through how this comes together.

The Ask: Your client, a B2B software company, wants to know whether to build or buy a new product capability.

Step 1: Formulate Your Recommendation#

After analysis, you conclude: Buy (specifically, acquire StartupCo for $25M).

Step 2: Develop Supporting Arguments (MECE)#

Why buy vs. build?

- Speed to market: Acquisition gets us to market in 6 months vs. 24 months for build

- Capability acquisition: StartupCo's team has expertise we'd take years to develop

- Financial logic: At $25M, acquisition is cheaper than internal development cost

Step 3: Structure the SCQA Opening#

Situation: We've identified conversational AI as a critical capability for our product roadmap. Customers are asking for it, and competitors are starting to offer it.

Complication: Building this internally would take 24 months and $30M, during which competitors will establish market position. We risk being a laggard in a space that's becoming table stakes.

Question: Should we build conversational AI capability internally or acquire it?

Answer: Acquire StartupCo for $25M. They have proven technology, a strong team, and are open to acquisition discussions.

Step 4: Build Out Each Argument#

Section 1: Speed to Market

- StartupCo's product is already in production with 15 customers

- Integration timeline is 6 months based on technical diligence

- Building internally would require hiring 12 engineers we don't currently have

Section 2: Capability Acquisition

- StartupCo's team includes 3 PhDs in NLP with publications in top venues

- Internal team would need 18+ months to reach equivalent expertise

- Retention package proposed for key personnel

Section 3: Financial Logic

- Internal build cost: $30M over 24 months

- Acquisition cost: $25M upfront

- NPV of acceleration: $15M (from earlier revenue capture)

Step 5: Create Slide Titles#

- "Recommend acquiring StartupCo for $25M to accelerate conversational AI capability"

- "Acquisition delivers capability 18 months faster than internal build"

- "StartupCo team brings deep NLP expertise we'd take years to develop"

- "Acquisition is $5M cheaper than build with $15M NPV from acceleration"

Each slide title tells the story. An executive reading just the titles understands the full argument.

Checklist: Applying the Pyramid Principle#

Use this before finalizing any presentation or document:

Structure

- Recommendation is stated in the first 30 seconds / first slide

- Supporting arguments are MECE (no overlap, nothing missing)

- Each argument is backed by specific evidence

- SCQA opening establishes context before the recommendation

Slides

- Every slide has an action title (complete sentence, not a topic)

- Each slide communicates exactly one message

- Reading only the titles tells the complete story

- Executive summary can stand alone

Clarity

- Recommendation uses active voice and specific language

- No more than 5 supporting arguments (group if needed)

- Audience knowledge gaps are addressed in the Situation

Summary#

The Pyramid Principle is the foundation of consulting communication:

- Lead with your recommendation (top of pyramid)

- Support with 3-5 MECE arguments (middle)

- Back each argument with evidence (bottom)

- Open with SCQA to establish context

- Use action titles that state your point, not your topic

You think from the bottom up. You present from the top down.

For tools that help you apply pyramid structure to presentations, Deckary's AI Slide Builder generates MBB-style slides from text descriptions, and the slide library offers 140+ pre-built consulting layouts.

Master it, and you'll never lose your audience on slide 14 again.

Build consulting slides in seconds

Describe what you need. AI generates structured, polished slides — charts and visuals included.

Try Free