Includes 2 slide variations

Free Root Cause Analysis PowerPoint Template

Part of our 143 template library. Install the free add-in to use it directly in PowerPoint.

What's Included

How to Use This Template

- 1Start with the observable problem or symptom

- 2Ask 'Why?' iteratively until reaching the root cause

- 3Document supporting facts at each level

- 4Use 5W1H to ensure comprehensive problem definition

- 5Stop when you reach a cause you can directly address

- 6Validate root cause with data before acting

When to Use This Template

- Operations troubleshooting

- Quality issue diagnosis

- Process failure analysis

- Customer complaint investigation

- Project post-mortems

- Continuous improvement initiatives

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Stopping at symptoms instead of root causes

- Accepting the first plausible explanation

- Not validating causes with data

- Asking 'why' to people instead of processes

- Focusing on blame instead of system improvement

Use This Template in PowerPoint

Get the Root Cause Analysis Template and 142 other consulting-grade templates with the free Deckary add-in.

Get Started FreeFree plan available. No credit card required.

Root Cause Analysis Template FAQs

Common questions about the root cause analysis template

Related Templates

Finding the Why Behind the Why

Root cause analysis is the discipline of not stopping at the obvious. When something goes wrong, the first explanation is almost never the real cause. It is a symptom, a proximate trigger, or a convenient scapegoat. The root cause lies deeper.

The techniques in this template—5 Whys and 5Ws & 1H—provide systematic approaches to drilling past symptoms to underlying causes. Addressing root causes prevents recurrence; addressing symptoms guarantees you will be back here again.

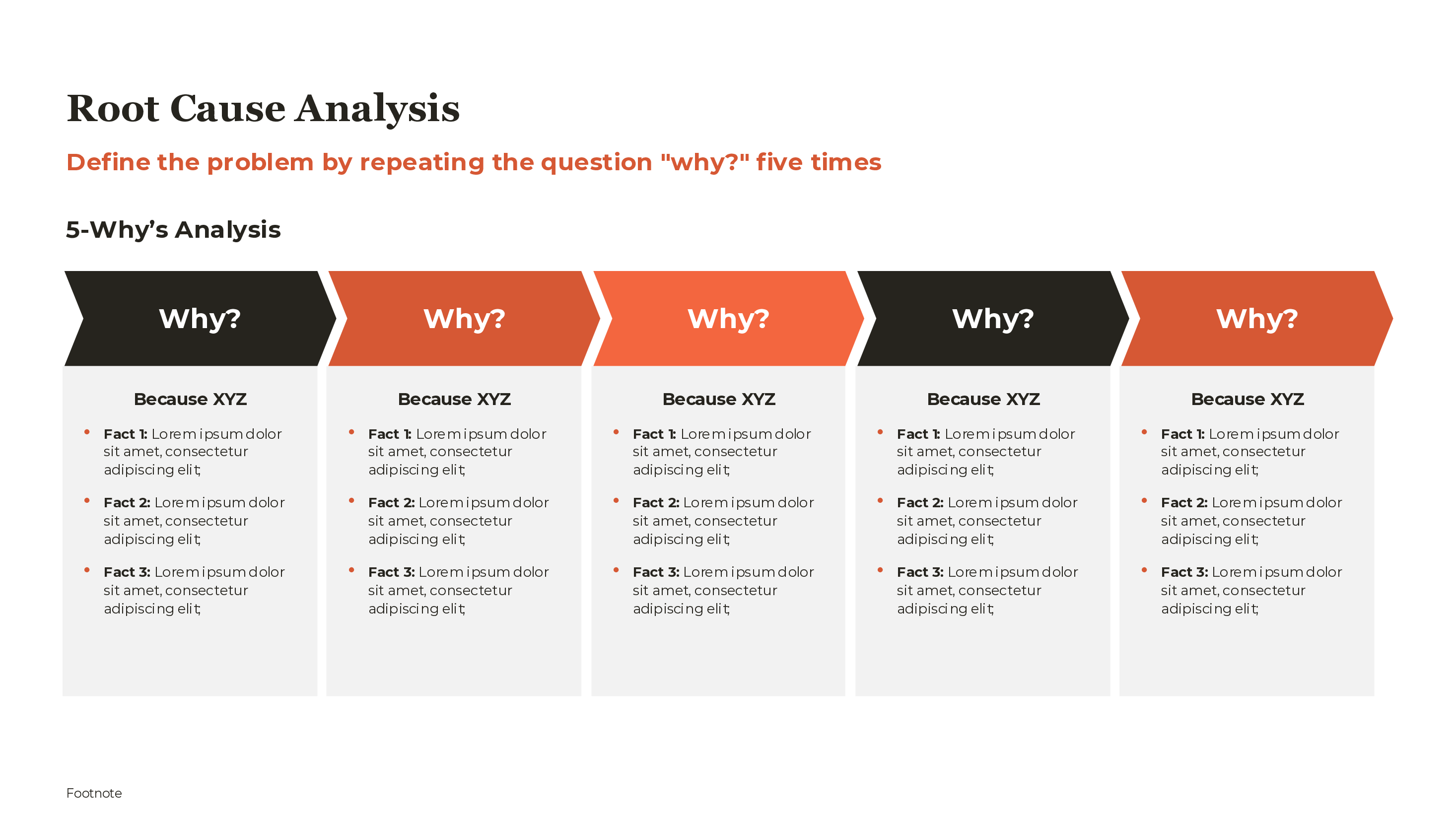

The 5 Whys Technique

Developed by Sakichi Toyoda and used extensively in Toyota's production system, the 5 Whys technique is elegantly simple: start with a problem and ask "Why?" five times.

Example:

- Problem: Customer received a defective product

- Why 1: The product was not inspected before shipping

- Why 2: The inspection step was skipped due to time pressure

- Why 3: The shipping deadline was set without accounting for inspection time

- Why 4: The order entry system does not calculate realistic shipping dates

- Why 5: The system was configured based on old production cycle times that no longer apply

The root cause is not a failed inspection—it is a system configuration issue that sets unrealistic deadlines. Fixing the system prevents future defects; adding more inspectors treats the symptom.

When to Stop Asking Why

Five is a guideline, not a rule. Stop when you reach a cause that is:

Actionable: You can do something about it. "People make mistakes" is not actionable. "The checklist does not include this step" is actionable.

Fundamental: Addressing this cause would prevent not just this incident but similar incidents. If fixing the cause only prevents this exact scenario, you have not gone deep enough.

Within your control: Eventually you hit causes outside your span of control (market conditions, regulatory requirements). Stop one level before that—at the last cause you can influence.

Verifiable: You should be able to validate the cause with data or investigation. If you cannot verify it, you are speculating.

Relationship to Fishbone (Ishikawa) Diagrams

While this template focuses on the 5 Whys approach, it complements the fishbone diagram methodology. The fishbone diagram (also called Ishikawa or cause-and-effect diagram) maps potential causes across categories—typically the 6Ms in manufacturing:

- Man (people)

- Machine (equipment)

- Method (process)

- Material (inputs)

- Measurement (data)

- Mother Nature (environment)

Use fishbone analysis to brainstorm all possible cause categories, then apply 5 Whys to drill into the most promising branches. The combination ensures both breadth and depth in your root cause investigation.

The 5Ws and 1H Framework

While 5 Whys drills vertically into causation, 5Ws and 1H ensures comprehensive horizontal coverage of the problem definition:

What: What exactly is the problem? What is happening that should not be, or not happening that should be? Be specific—"Quality issues" is not a problem statement; "15% defect rate on Product Line A" is.

Why: Why is this a problem? What is the impact? This establishes significance and prioritization. A 15% defect rate matters differently if it affects safety versus cosmetics.

When: When does the problem occur? Always, or only under certain conditions? Did it start recently? Is there a pattern (time of day, day of week, seasonally)? Temporal patterns often reveal causes.

Who: Who is affected? Who is involved when it happens? Are certain teams, shifts, or individuals associated with the problem? Note: this is for diagnosis, not blame.

Where: Where does the problem occur? Specific locations, machines, processes, or stages? Geographic or departmental patterns can point to local causes.

How: How does the problem manifest? What is the sequence of events? How is it currently being handled? Understanding the mechanism helps identify intervention points.

Combining the Frameworks

5Ws and 1H and 5 Whys work well together. Use 5Ws and 1H first to comprehensively define and scope the problem. Then apply 5 Whys to drill into the causal chain.

The 5Ws and 1H answers often reveal which "Why" chain to pursue. If "When" reveals the problem only started after a process change, your 5 Whys should explore that change. If "Where" shows the problem is isolated to one facility, start your causal inquiry there.

Common 5 Whys Pitfalls

Stopping too early: The first plausible cause feels satisfying, but it is often not the root. Keep asking until you hit something fundamental.

Multiple causes: Real problems often have multiple contributing factors. If your 5 Whys branches, follow each branch. You may have multiple root causes to address.

Blame-seeking: Asking "why" to a person ("Why did you skip the inspection?") invites defensiveness and blame. Ask "why" to processes and systems ("Why was the inspection skipped?").

Speculation without data: Each "because" should be verifiable. If you are guessing, you need to investigate before proceeding.

Circular logic: Sometimes the chain loops back ("Why A? Because B. Why B? Because A."). This indicates you need to break the frame and look for a third factor.

Validating Root Causes

Before investing resources in a fix, validate that you have found the actual root cause:

Correlation test: Does the proposed cause actually correlate with the problem? When the cause is present, does the problem occur? When absent, does it not occur?

Mechanism test: Is there a plausible mechanism connecting cause to effect? Can you explain how the cause produces the symptom?

Expert review: Do people with deep domain knowledge agree this is the root cause? Skepticism from experts suggests you may have missed something.

Small experiment: Can you test the hypothesis with a limited intervention? If fixing the supposed root cause in one area eliminates the problem there, you have validation.

From Root Cause to Countermeasure

Identifying the root cause is not the end—it is the midpoint. The purpose is to develop countermeasures that prevent recurrence:

Immediate countermeasure: What can you do right now to stop the bleeding? This addresses the symptom while you work on the permanent fix.

Permanent countermeasure: What systemic change addresses the root cause? This might involve process redesign, system changes, training, or organizational adjustments.

Verification plan: How will you confirm the countermeasure worked? Define metrics and monitoring periods.

Horizontal deployment: Does this root cause exist elsewhere? Should the countermeasure be applied more broadly?

Building the Analysis Slides

For 5 Whys, use a horizontal chevron progression showing the causal chain from left to right. Each chevron contains the "because" statement, with supporting facts below. Color code from red (problem) through orange to green (root cause and solution).

For 5Ws and 1H, use a structured table or vertical list with each question as a row. Include columns for the answer, supporting evidence, and implications or considerations.

Both layouts should conclude with a clear statement of the root cause and proposed countermeasures.

For real-world examples across multiple techniques, see our Root Cause Analysis Examples, Fishbone Diagram Examples, and 5 Whys Examples.

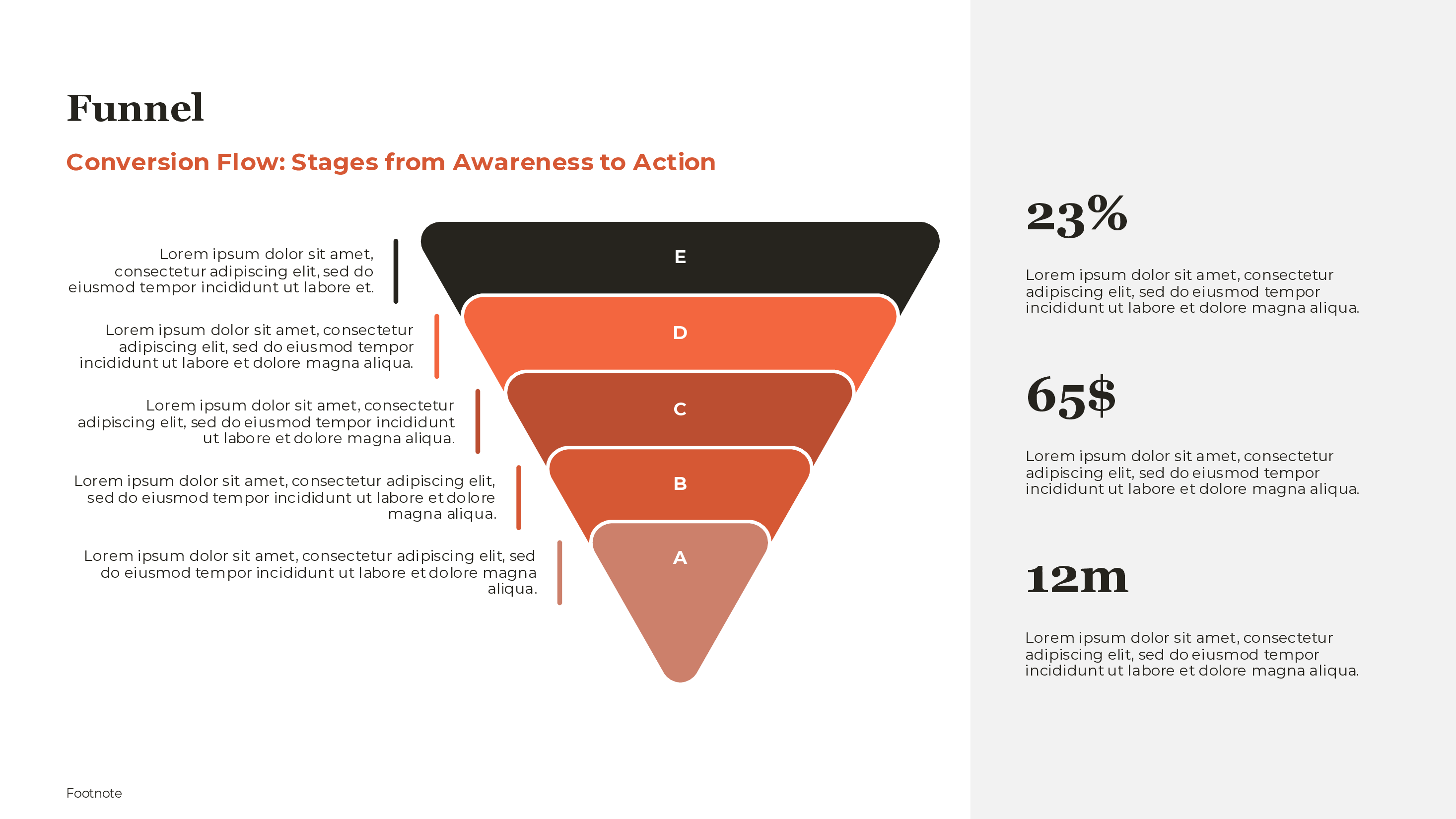

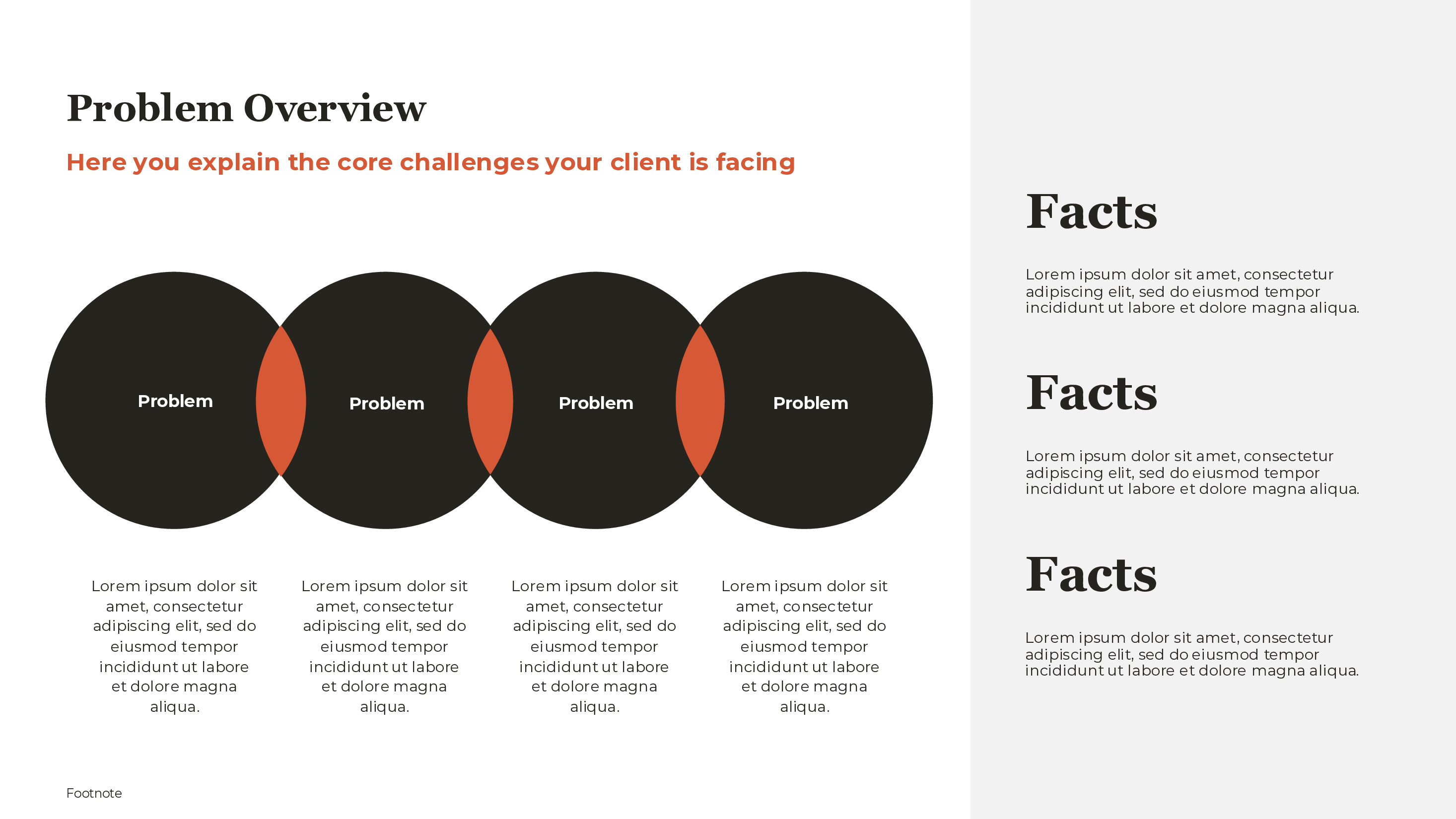

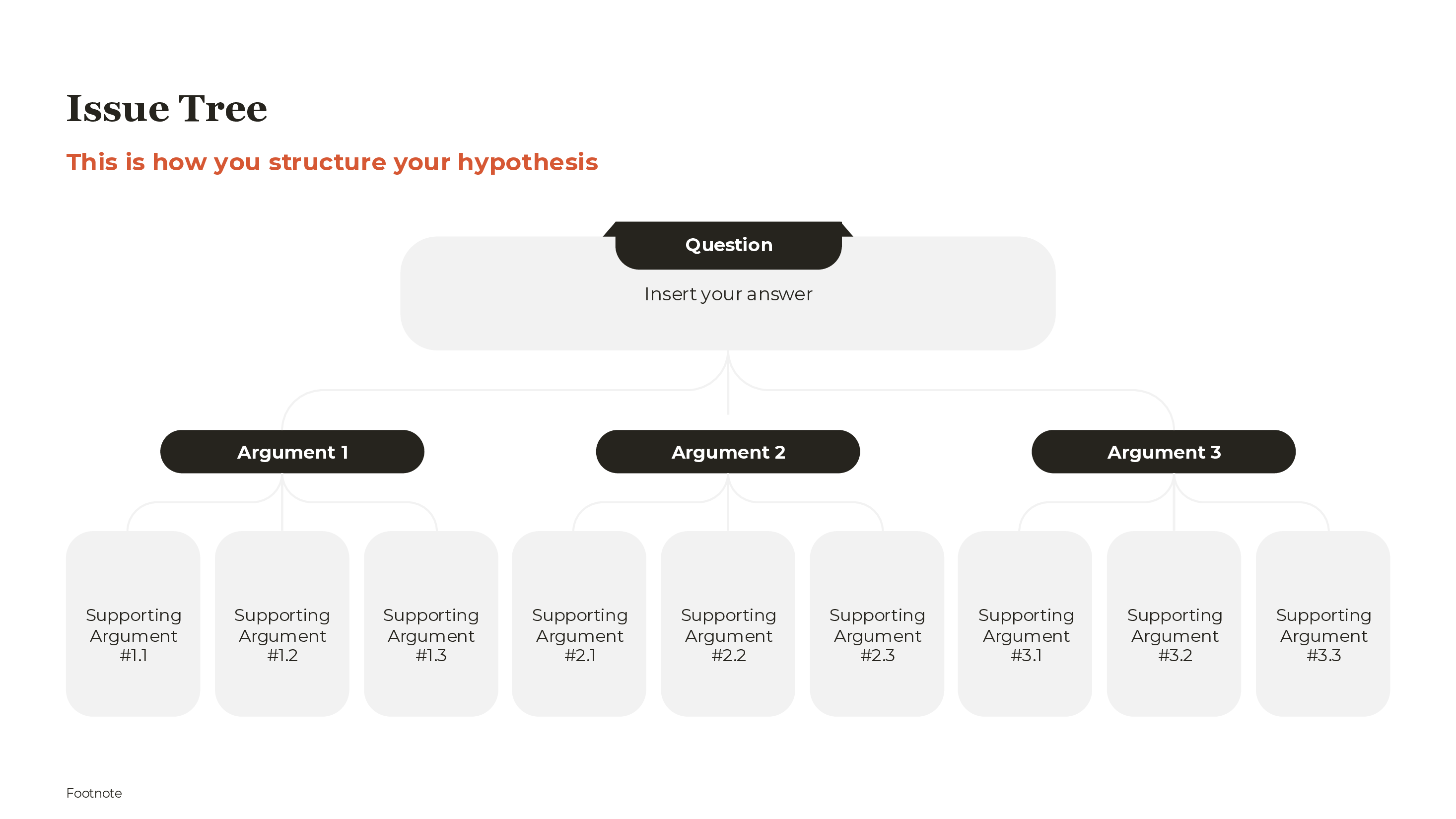

For related frameworks, see our issue tree template for problem decomposition, problem statement template for framing challenges, and conversion funnel template for process analysis.