Problem Solving Frameworks: 6 Consulting Methods With Worked Examples

Problem solving frameworks used at McKinsey, BCG, and Bain. Covers MECE, issue trees, hypothesis-driven approach, Pyramid Principle, and when to use each.

Problem solving frameworks are the operating system behind every consulting engagement. McKinsey, BCG, and Bain each train their analysts on structured approaches that turn ambiguous business problems into actionable recommendations -- and the same frameworks work for any team facing complex decisions.

After applying these frameworks across 80+ strategy, operations, and due diligence engagements, we have found that the difference between a productive problem-solving session and a circular debate is almost always structural. Teams that decompose before analyzing reach better answers faster than teams that brainstorm without a framework.

This guide covers six problem solving frameworks with worked examples, a decision table for choosing the right one, the McKinsey problem-solving process end to end, and the mistakes that derail even experienced teams. For the broader context, see our Strategic Frameworks Guide.

The McKinsey Problem Solving Process#

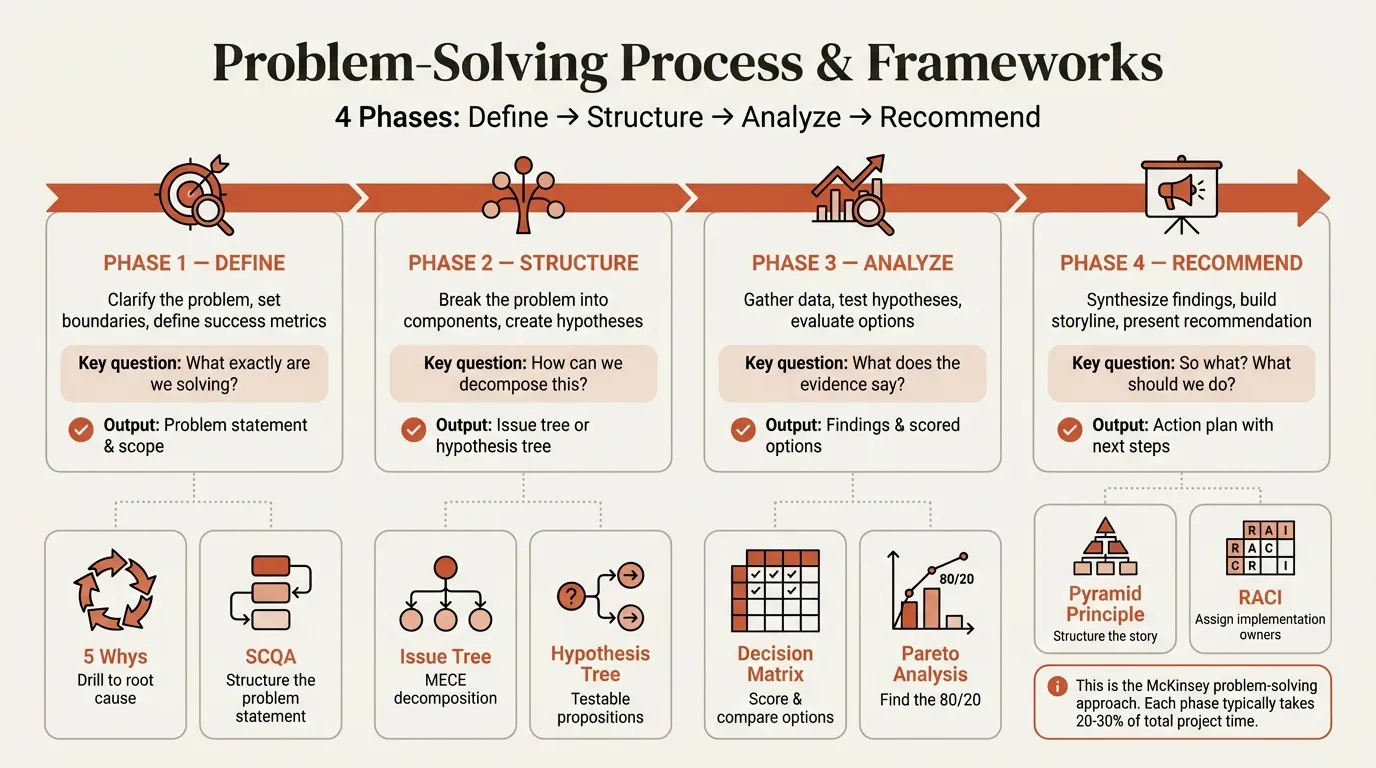

Before diving into individual frameworks, it helps to understand how they fit together. McKinsey's seven-step problem-solving process is the backbone that most consulting firms adapt:

- Define the problem. Write a specific, bounded problem statement. "Revenue is declining" is not a problem statement. "North American SaaS revenue declined 12% YoY in Q3 despite 8% growth in new logos" is.

- Structure the problem. Break it into MECE components using an issue tree.

- Prioritize issues. Not all branches matter equally. Identify which issues drive the most impact.

- Develop a work plan. Assign analyses to each priority issue with clear hypotheses to test.

- Conduct analyses. Gather data and test each hypothesis.

- Synthesize findings. Use the Pyramid Principle to distill analysis into a governing insight.

- Develop recommendations. Translate findings into actions with owners, timelines, and expected impact.

The process is not linear. Synthesis should happen continuously -- McKinsey calls it the "Day 1 answer," where teams articulate their best hypothesis from the start and refine it as data comes in.

Problem Solving Frameworks: The Six Core Methods#

1. MECE (Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive)#

MECE is the foundational principle underneath nearly every other framework on this list. Developed by Barbara Minto at McKinsey in the late 1960s, it ensures that when you break a problem into parts, no parts overlap (mutually exclusive) and no parts are missing (collectively exhaustive).

When to use it: Every time you decompose a problem, segment a market, or categorize causes.

Worked example: A retail chain's same-store sales are declining. A MECE breakdown of revenue drivers:

- Traffic (number of customers entering stores)

- Conversion (percentage who purchase)

- Average basket size (revenue per transaction)

These three factors are mutually exclusive -- each captures a different driver -- and collectively exhaustive -- together they fully explain revenue per store. If you added "online sales" as a fourth category, it would overlap with traffic and conversion, breaking the ME principle. If you left out basket size, you would miss a critical lever, breaking the CE principle.

2. Issue Trees#

Issue trees take the MECE principle and make it visual. They are the primary problem-solving tool at McKinsey, BCG, and Bain, breaking a complex question into progressively smaller sub-questions until you reach hypotheses you can test with data.

When to use it: Structuring any complex business problem before analysis begins.

Worked example: Question -- "Why is our enterprise sales cycle lengthening?"

- Lead quality declining?

- Marketing generating less qualified leads?

- ICP definition outdated?

- Sales process inefficiency?

- Too many approval stages?

- Demo-to-proposal handoff taking longer?

- Buyer behavior shifting?

- More stakeholders in buying committee?

- Budget cycles changing?

- Competitive pressure increasing?

- New entrants extending evaluation periods?

- Incumbent vendors offering retention deals?

Each branch is MECE at its level. The team can now assign analysts to the highest-priority branches rather than investigating everything at once. For related examples of tree-based analysis, see our guide to Decision Tree Examples.

3. Hypothesis-Driven Approach#

Where issue trees map the problem space, the hypothesis-driven approach starts with an answer and works backward. Instead of open-ended exploration, you form an initial hypothesis on day one and design analyses specifically to prove or disprove it.

When to use it: When you need speed, when you have enough domain knowledge to form a reasonable starting hypothesis, or when stakeholders need early directional answers.

Worked example: A logistics company's delivery costs are 18% above industry benchmarks.

- Hypothesis: "Last-mile delivery costs are the primary driver because our route density is 40% below competitors in suburban markets."

- Test 1: Segment costs by delivery phase (first-mile, linehaul, last-mile). Result: last-mile accounts for 62% of total cost vs. 48% industry average. Hypothesis supported.

- Test 2: Compare route density by market type. Result: suburban route density is 35% below benchmark; urban density is on par. Hypothesis refined.

- Test 3: Model cost impact of increasing suburban route density by 20%. Result: projected savings of 9% on total delivery cost. Hypothesis validated.

The risk of this approach is confirmation bias -- designing analyses that only support your hypothesis. The discipline is to actively seek disconfirming evidence at each step.

4. The Pyramid Principle#

The Pyramid Principle, from Barbara Minto's landmark book, is not strictly a problem-solving framework but a communication framework that shapes how you present your solution. It has become inseparable from consulting problem solving because structuring your thinking for communication forces clarity.

The rule: Start with the answer (the governing thought), then support it with key arguments, each supported by evidence. Your audience gets the conclusion first and drills into supporting detail only if needed.

When to use it: Synthesizing findings, writing executive memos, structuring slide decks.

Worked example: Instead of presenting 40 slides of analysis that build to a conclusion on slide 41:

- Governing thought: "We should enter the Southeast Asian market through a joint venture with a local distributor, targeting $15M revenue in year one."

- Supporting argument 1: Market opportunity is $2.1B and growing 14% annually -- large enough to justify entry.

- Supporting argument 2: JV structure reduces capital risk by 60% vs. greenfield while providing local regulatory expertise.

- Supporting argument 3: Three qualified distributor partners identified, each with 200+ enterprise client relationships.

Each supporting argument follows the same MECE, evidence-backed structure underneath. This is how McKinsey and most consulting firms structure their deliverables.

5. Root Cause Analysis#

Root cause analysis (RCA) is the diagnostic framework for understanding why something went wrong. While MECE and issue trees help you map a problem space, RCA specifically drills from symptoms to underlying causes using methods like 5 Whys, fishbone diagrams, and fault tree analysis.

When to use it: Post-incident investigations, operational performance declines, quality issues, recurring failures.

Worked example: A SaaS company's customer churn doubled from 8% to 16% in two quarters. Using the 5 Whys:

- Why is churn increasing? Customers cite "lack of value" in exit surveys.

- Why do they perceive lack of value? Usage of the core analytics module dropped 30%.

- Why did usage drop? A UI redesign moved the analytics dashboard from the homepage to a secondary menu.

- Why was the dashboard moved? The product team prioritized a new feature and needed homepage real estate.

- Why was the trade-off not evaluated? No framework for assessing impact on existing user workflows before making navigation changes.

Root cause: Missing product change-impact assessment process, not the UI redesign itself. For complete walkthroughs with five worked cases, see our Root Cause Analysis Examples, and for a ready-to-use worksheet, see the Root Cause Analysis Template.

6. Design Thinking#

Design thinking starts from user needs rather than business metrics. It is the most divergent framework on this list -- instead of narrowing toward a single answer, it deliberately generates multiple possible solutions before converging.

When to use it: Ambiguous problems where the problem definition itself is unclear, user-centered innovation, new product development.

The five stages:

- Empathize: Interview users, observe behavior, identify unmet needs.

- Define: Synthesize observations into a specific problem statement.

- Ideate: Generate multiple solutions without filtering.

- Prototype: Build low-fidelity versions of the top ideas.

- Test: Validate with real users and iterate.

Worked example: A bank's mobile app has low adoption among small business owners. Instead of assuming the problem is feature gaps, the team interviews 30 business owners and discovers that most manage cash flow in spreadsheets because the app's categorization does not match how they think about expenses. The solution is not more features but a recategorization that mirrors real workflows -- something no amount of internal analysis would have surfaced.

Continue reading: Agenda Slide PowerPoint · Flowchart in PowerPoint · Pitch Deck Guide

Free consulting slide templates

SWOT, competitive analysis, KPI dashboards, and more — ready-made PowerPoint templates built to consulting standards.

Framework Comparison Table#

| Framework | Best For | Time Required | Skill Level | Output Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MECE | Decomposing any problem | 30-60 min | Beginner | Categorized structure |

| Issue Trees | Mapping complex problems | 1-3 hours | Intermediate | Visual problem map |

| Hypothesis-Driven | Speed to answer | 1-2 days | Advanced | Tested recommendation |

| Pyramid Principle | Communicating findings | 2-4 hours | Intermediate | Structured narrative |

| Root Cause Analysis | Diagnosing failures | 4-40 hours | Intermediate | Verified root cause |

| Design Thinking | Ambiguous, user-centered problems | 2-6 weeks | Advanced | Validated prototype |

Which Framework for Which Problem Type#

The decision depends on three dimensions: how well-defined the problem is, whether the work is analytical or creative, and the time horizon.

| Problem Characteristics | Recommended Frameworks | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Well-defined, analytical, urgent | Hypothesis-driven + MECE | "Why did Q3 revenue miss by 15%?" |

| Well-defined, analytical, strategic | Issue tree + Root cause analysis | "How do we reduce manufacturing costs by 20%?" |

| Ambiguous, analytical, strategic | MECE + Issue tree + Hypothesis-driven | "Should we enter the European market?" |

| Ambiguous, creative, strategic | Design thinking + MECE | "How might we reimagine the onboarding experience?" |

| Post-incident, diagnostic | Root cause analysis + Issue tree | "Why did the product launch fail?" |

| Communication and synthesis | Pyramid Principle + MECE | "Present our findings to the board" |

Combining Frameworks in Practice#

In a real consulting engagement, you rarely use a single framework. A typical 8-week strategy project might combine them like this:

Week 1 -- Define and structure. Use MECE to decompose the client's question into an issue tree. Simultaneously form a day-one hypothesis based on initial data and interviews.

Weeks 2-5 -- Analyze. Run hypothesis-driven analyses on the highest-priority branches. If investigating an operational failure, apply root cause analysis on that branch. If exploring a new market opportunity, apply elements of design thinking (user interviews, needs mapping).

Weeks 6-7 -- Synthesize. Use the Pyramid Principle to structure findings. The governing thought comes from your validated (or revised) hypothesis. Supporting arguments map to the issue tree branches.

Week 8 -- Recommend. Deliver recommendations structured as Pyramid Principle presentations, with each recommendation supported by the specific analyses that validated it.

The sequence matters. Structuring before analyzing prevents wasted effort. Synthesizing with the Pyramid Principle forces you to convert analysis into recommendations rather than presenting raw findings.

Common Problem Solving Mistakes#

After reviewing how teams apply these problem solving frameworks, these errors appear repeatedly:

Jumping to solutions before structuring. The most common mistake. A team identifies a plausible cause in the first meeting and spends weeks building the solution without ever verifying that they are solving the right problem. Issue trees and MECE exist specifically to prevent this.

Not being MECE. Overlapping categories lead to double-counting. Missing categories lead to blind spots. If your revenue decomposition includes "new customers" and "enterprise customers," those overlap -- a new enterprise customer gets counted twice. See our SWOT Analysis Examples for how this principle applies to strategic assessment.

Presenting analysis instead of recommendations. Teams often deliver 80 pages of analysis with no clear "so what." The Pyramid Principle solves this: lead with the recommendation, support it with evidence. Executives do not want to read your journey -- they want your conclusion.

Using one framework when you need two. A hypothesis-driven approach without an issue tree risks tunnel vision. An issue tree without prioritization wastes resources on low-impact branches. Root cause analysis without data verification produces plausible but unconfirmed causes.

Confusing frameworks with answers. MECE does not tell you what to do -- it tells you how to organize your thinking. Teams sometimes spend days perfecting their issue tree structure and never get to the analysis. The framework is a tool, not the deliverable.

Key Takeaways#

- The McKinsey problem-solving process (define, structure, prioritize, plan, analyze, synthesize, recommend) provides the end-to-end workflow. Individual frameworks plug into specific steps.

- MECE is the foundation. Every issue tree, every root cause decomposition, every Pyramid Principle structure should be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive.

- Match the framework to the problem: hypothesis-driven for speed, issue trees for complexity, root cause analysis for diagnostics, design thinking for ambiguity.

- Real engagements combine multiple frameworks. Structure with MECE and issue trees, analyze with hypothesis-driven methods, communicate with the Pyramid Principle.

- The most common mistake is not choosing the wrong framework -- it is skipping the structuring step entirely and jumping to solutions.

Build consulting slides in seconds

Describe what you need. AI generates structured, polished slides — charts and visuals included.

Try Free