GE-McKinsey Matrix: The Definitive Guide to Portfolio Strategy

GE-McKinsey Matrix explained with scoring methodology, weighted factors, and strategic implications. Prioritize business units across the nine-box grid.

The GE-McKinsey Matrix is the portfolio strategy framework that replaced gut instinct with structured scoring at one of the world's largest conglomerates. When General Electric asked McKinsey in the early 1970s to help prioritize investment across 150+ business units, the result was a nine-box grid that remains the standard for multi-factor portfolio analysis in corporate strategy.

After applying the GE-McKinsey matrix in 30+ portfolio reviews, due diligence projects, and corporate strategy engagements, we have found that the framework's value depends almost entirely on the rigor of the scoring process. A poorly weighted nine-box grid is worse than a simple BCG matrix. A well-constructed one reveals allocation decisions that single-metric frameworks miss.

This guide covers the full methodology: how to select and weight factors, how to score business units, what each of the nine cells implies strategically, and how to avoid the scoring pitfalls that undermine the framework. For a broader overview of strategy frameworks, see our Strategic Frameworks Guide.

Origin of the GE-McKinsey Matrix#

In the late 1960s, General Electric managed one of the most diversified portfolios in corporate history: jet engines, light bulbs, nuclear reactors, consumer appliances, financial services, and dozens more. The company needed a systematic way to decide which businesses deserved capital and which should be divested.

GE had already experimented with the BCG matrix, the growth-share framework developed by Bruce Henderson at BCG, but found its two single-variable axes (market growth rate and relative market share) too reductive for a portfolio spanning unrelated industries. A jet engine division and a consumer electronics division cannot be meaningfully compared on market share alone.

McKinsey's solution, as described in McKinsey's own portfolio planning literature, was to replace single metrics with composite scores built from multiple weighted factors. Instead of asking "Is this market growing?" the framework asks "How attractive is this industry across all the dimensions that matter?" The result was the nine-box matrix -- a tool that could accommodate qualitative judgment alongside quantitative data, calibrated differently for different industries.

How the GE-McKinsey Matrix Works#

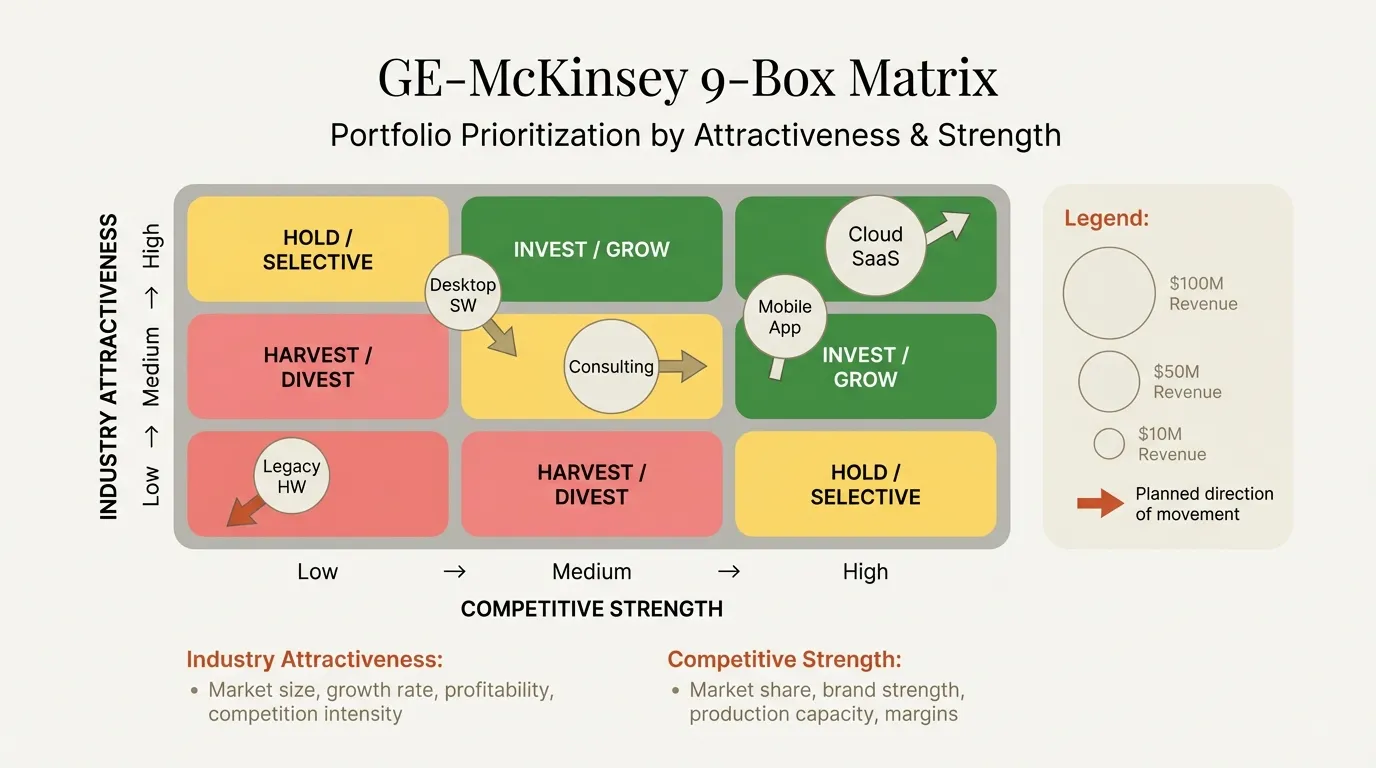

The framework plots business units on a 3x3 grid using two composite dimensions:

- Y-axis: Industry Attractiveness -- a weighted score reflecting how desirable it is to operate in a given industry, independent of the company's current position in it.

- X-axis: Competitive Strength -- a weighted score reflecting how well-positioned the company is to compete in that industry.

Each axis is divided into three zones (High, Medium, Low), creating nine cells. The critical difference from simpler frameworks is that both axes are composite -- weighted averages of multiple factors chosen based on the specific strategic context.

Selecting and Weighting Factors for the GE-McKinsey Matrix#

The scoring process is where the GE-McKinsey matrix either delivers insight or collapses into pseudo-precision. Factor selection and weighting are the most important steps.

Industry Attractiveness Factors#

These factors evaluate the industry itself, not the company's position in it:

| Factor | What It Measures | Typical Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Market size | Total addressable revenue | 0.15-0.20 |

| Market growth rate | Annual growth trajectory | 0.15-0.20 |

| Industry profitability | Average margins across players | 0.10-0.20 |

| Competitive intensity | Number and aggressiveness of rivals | 0.10-0.15 |

| Technological stability | Rate of disruptive change | 0.05-0.10 |

| Regulatory environment | Barriers, compliance costs, policy risk | 0.05-0.15 |

| Cyclicality | Revenue volatility through economic cycles | 0.05-0.10 |

Competitive Strength Factors#

These factors evaluate the company's position within the industry:

| Factor | What It Measures | Typical Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Market share | Relative position vs. competitors | 0.15-0.20 |

| Brand strength | Recognition, trust, pricing power | 0.10-0.15 |

| Production capacity | Scale and cost advantages | 0.10-0.15 |

| Profit margins (relative) | Margins vs. industry average | 0.10-0.15 |

| Technological capability | R&D strength, IP portfolio | 0.10-0.15 |

| Management quality | Leadership depth and track record | 0.05-0.10 |

| Distribution network | Channel access and coverage | 0.05-0.15 |

Weights must sum to 1.0 per axis. The specific weights depend on the company's strategic priorities. A PE-backed company focused on near-term cash generation will weight profitability and cyclicality higher. A company pursuing long-term growth will weight market size and growth rate higher.

Weighting Principles#

Three rules prevent the most common scoring failures:

- No factor should exceed 0.25 weight. If one factor dominates the composite score, you are effectively back to a single-metric framework.

- Weights should vary by industry context. Technology capability matters more in semiconductors than in cement. Use the same factor list across business units for consistency, but adjust weights when industries differ fundamentally.

- Get alignment on weights before scoring. Lock in weights and factors with leadership before anyone sees results. This eliminates the "let me re-weight to change my score" problem.

Continue reading: Agenda Slide PowerPoint · Flowchart in PowerPoint · Pitch Deck Guide

Free consulting slide templates

SWOT, competitive analysis, KPI dashboards, and more — ready-made PowerPoint templates built to consulting standards.

Scoring Methodology#

Score each business unit on every factor using a 1-5 scale, then calculate composite scores:

| Score | Industry Attractiveness | Competitive Strength |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Highly attractive (large, growing, profitable) | Dominant position (market leader, cost leader) |

| 4 | Attractive on most dimensions | Strong position with minor gaps |

| 3 | Moderately attractive (mixed signals) | Comparable to competitors |

| 2 | Below average on most dimensions | Weak position with significant gaps |

| 1 | Unattractive (shrinking, low-margin) | Very weak (subscale, losing share) |

Composite Score = Sum of (Factor Score x Factor Weight), yielding a value between 1.0 and 5.0 for each axis. Plot the business unit at the intersection.

Example -- Industrial Coatings Division:

| Industry Attractiveness Factor | Weight | Score | Weighted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market size | 0.20 | 4 | 0.80 |

| Market growth rate | 0.20 | 3 | 0.60 |

| Industry profitability | 0.15 | 4 | 0.60 |

| Competitive intensity | 0.15 | 2 | 0.30 |

| Technological stability | 0.10 | 4 | 0.40 |

| Regulatory environment | 0.10 | 3 | 0.30 |

| Cyclicality | 0.10 | 2 | 0.20 |

| Total | 1.00 | 3.20 |

With a competitive strength score of 3.60 (calculated the same way), this division plots at (3.60, 3.20) -- the center of the grid, placing it in the Selectivity zone. The strategic implication: manage for earnings, invest selectively where competitive strength can improve, but do not commit growth-level capital.

The Nine Cells and Their Strategic Implications#

The nine-box grid divides into three strategic zones:

Invest/Grow Zone (Top-Left)#

| Cell | Industry Attractiveness | Competitive Strength | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-left | High | High | Invest heavily for growth, protect position |

| Top-center | High | Medium | Build strength, challenge for leadership |

| Center-left | Medium | High | Invest selectively, leverage existing strengths |

Business units here justify aggressive capital allocation -- capacity expansion, acquisitions, R&D, talent recruitment. Protect these units from corporate cost-cutting.

Selectivity/Earnings Zone (Diagonal)#

| Cell | Industry Attractiveness | Competitive Strength | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-right | High | Low | Invest selectively or divest -- assess if strength can be built |

| Center-center | Medium | Medium | Manage for earnings, selective investment only |

| Bottom-left | Low | High | Harvest cash, minimize new investment |

The diagonal is where the hardest decisions live. Fund specific initiatives with clear ROI hurdles rather than broad investment. Set explicit milestones for deciding whether to move the unit toward Invest/Grow or Harvest/Divest.

Harvest/Divest Zone (Bottom-Right)#

| Cell | Industry Attractiveness | Competitive Strength | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center-right | Medium | Low | Harvest cash, limit investment |

| Bottom-center | Low | Medium | Harvest or divest, no new investment |

| Bottom-right | Low | Low | Divest immediately |

These units consume resources that would generate better returns elsewhere. Reduce fixed costs, sell to a buyer who can extract more value, and avoid the sunk-cost trap of continuing investment because "we've already spent so much."

Worked Example: Multi-Business Portfolio#

Consider a hypothetical conglomerate with four divisions:

| Division | Revenue | Industry Attractiveness | Competitive Strength | Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cloud Services | $800M | 4.4 | 3.8 | Invest/Grow |

| Industrial Coatings | $1.2B | 3.2 | 3.6 | Selectivity |

| Print Media Solutions | $400M | 1.8 | 2.4 | Harvest/Divest |

| Healthcare Diagnostics | $600M | 4.1 | 2.2 | Selectivity (top-right) |

Cloud Services gets the largest share of growth capital -- highly attractive industry, strong position. Industrial Coatings generates cash to fund Cloud growth through selective investment in automation. Print Media should be divested -- structurally declining industry with no competitive differentiation.

Healthcare Diagnostics is the most interesting decision. The industry is highly attractive, but the division is competitively weak. Can we build strength through acquisition or R&D, or is the gap too large? This is where the GE-McKinsey matrix earns its complexity premium: the BCG matrix would classify this as a Question Mark, which is correct but unhelpful. The nine-box grid shows the gap is in competitive strength specifically, implying capability building is the right investment type.

GE-McKinsey Matrix vs. BCG Matrix#

| Dimension | GE-McKinsey Matrix | BCG Matrix |

|---|---|---|

| Grid size | 3x3 (nine cells) | 2x2 (four quadrants) |

| Y-axis | Industry attractiveness (composite) | Market growth rate (single metric) |

| X-axis | Competitive strength (composite) | Relative market share (single metric) |

| Number of factors | 10-16 weighted factors | 2 metrics |

| Subjectivity | High (factor selection, weighting, scoring) | Low (data-driven) |

| Best for | Diversified portfolios with dissimilar industries | Quick screening, portfolios in related industries |

| Limitations | Scoring bias, time-intensive, false precision | Oversimplifies, ignores non-share advantages |

Start with the BCG matrix for initial portfolio screening. Graduate to the GE-McKinsey matrix when business units operate in fundamentally different industries or when competitive advantage depends on factors beyond market share. For worked BCG examples, see our BCG Matrix Examples guide.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them#

Scoring inflation. Business unit leaders score their own divisions generously. The result is a grid where everything clusters in Invest/Grow. Fix: use an independent scoring team and score relative to the best competitor, not internal benchmarks.

Equal weighting by default. Teams that skip the weighting discussion assume every factor matters equally. This is almost never true. Fix: debate weights explicitly before scoring. The conversation about weights is often more valuable than the final grid.

Static analysis. A single snapshot misses trajectory. Fix: plot both current position and a 12-24 month projected position using arrows on the grid.

Ignoring interdependencies. The framework evaluates units independently, but a weak division might supply critical components to a strong one. Fix: map cross-unit dependencies before making divestiture decisions.

Building the GE-McKinsey Matrix in Presentations#

The framework's visual complexity makes it challenging to present. Three formatting principles keep the slide readable: use revenue-sized bubbles for a third dimension, color-code zones (green for Invest/Grow, yellow for Selectivity, red for Harvest/Divest), and include a supporting slide with the factor-weight-score table to show the methodology behind the grid positions.

For a ready-made slide layout with pre-formatted zones and scoring tables, see our GE-McKinsey Matrix Template. For building competitive analysis slides that complement portfolio strategy, use a Competitive Analysis Template to show where individual units stand against direct competitors. Tools like Deckary speed up the bubble chart overlay and nine-box grid alignment that are tedious to build manually in PowerPoint.

As Harvard Business Review notes in its analysis of portfolio planning tools, the framework works best for annual portfolio reviews at diversified corporations, M&A target screening, capital allocation decisions, and PE portfolio management. For growth strategy in a single business, the Ansoff Matrix is a better fit.

Summary#

The GE-McKinsey matrix is the most rigorous portfolio strategy framework available to corporate strategists. Its value comes from forcing multi-factor evaluation where simpler tools rely on single metrics.

- Two composite axes -- industry attractiveness and competitive strength, each built from 5-8 weighted factors

- Scoring rigor matters more than the grid -- factor selection, weighting, and calibration are where the real strategic thinking happens

- Three zones drive allocation -- Invest/Grow (top-left), Selectivity/Earnings (diagonal), Harvest/Divest (bottom-right)

- Use it after the BCG matrix -- start with a quick BCG screen, then graduate to GE-McKinsey when you need multi-factor nuance

- Watch for scoring inflation -- independent scoring and relative-to-competitor calibration prevent the grid from becoming a self-congratulation exercise

For ready-made slide layouts, start with our GE-McKinsey Matrix Template. For the broader framework selection process, see our Strategic Frameworks Guide.

Build consulting slides in seconds

Describe what you need. AI generates structured, polished slides — charts and visuals included.

Try Free