Decision Tree Analysis: A Quantitative Guide to Expected Value Decisions

Decision tree analysis methodology with EMV calculations, fold-back technique, sensitivity analysis, and value of perfect information for business decisions.

Decision tree analysis is the standard quantitative method for evaluating decisions under uncertainty when outcomes can be assigned probabilities and monetary values. Unlike qualitative frameworks that rank options by intuition, decision tree analysis produces a single number -- the expected monetary value -- that tells you which path maximizes risk-adjusted returns.

The methodology was formalized by Howard Raiffa at Harvard in the 1960s and has since become foundational in consulting, project management, and corporate finance. The core technique -- assigning probabilities, calculating expected values, and folding back the tree -- is straightforward, but applying it rigorously requires understanding how to assess probabilities, perform sensitivity analysis, and interpret results in the context of risk tolerance.

After applying decision tree analysis across 90+ investment committee, M&A, and go/no-go engagements, we have found that the methodology consistently outperforms unstructured deliberation when decisions involve sequential uncertainty and quantifiable payoffs. This guide covers the analytical methodology: node types and tree structure, EMV calculation with a worked example, the fold-back technique, value of perfect information, sensitivity analysis, and how decision tree analysis compares to other quantitative methods. For worked business examples, see our Decision Tree Examples guide. For the broader toolkit, see our Strategic Frameworks Guide.

How Decision Tree Analysis Works#

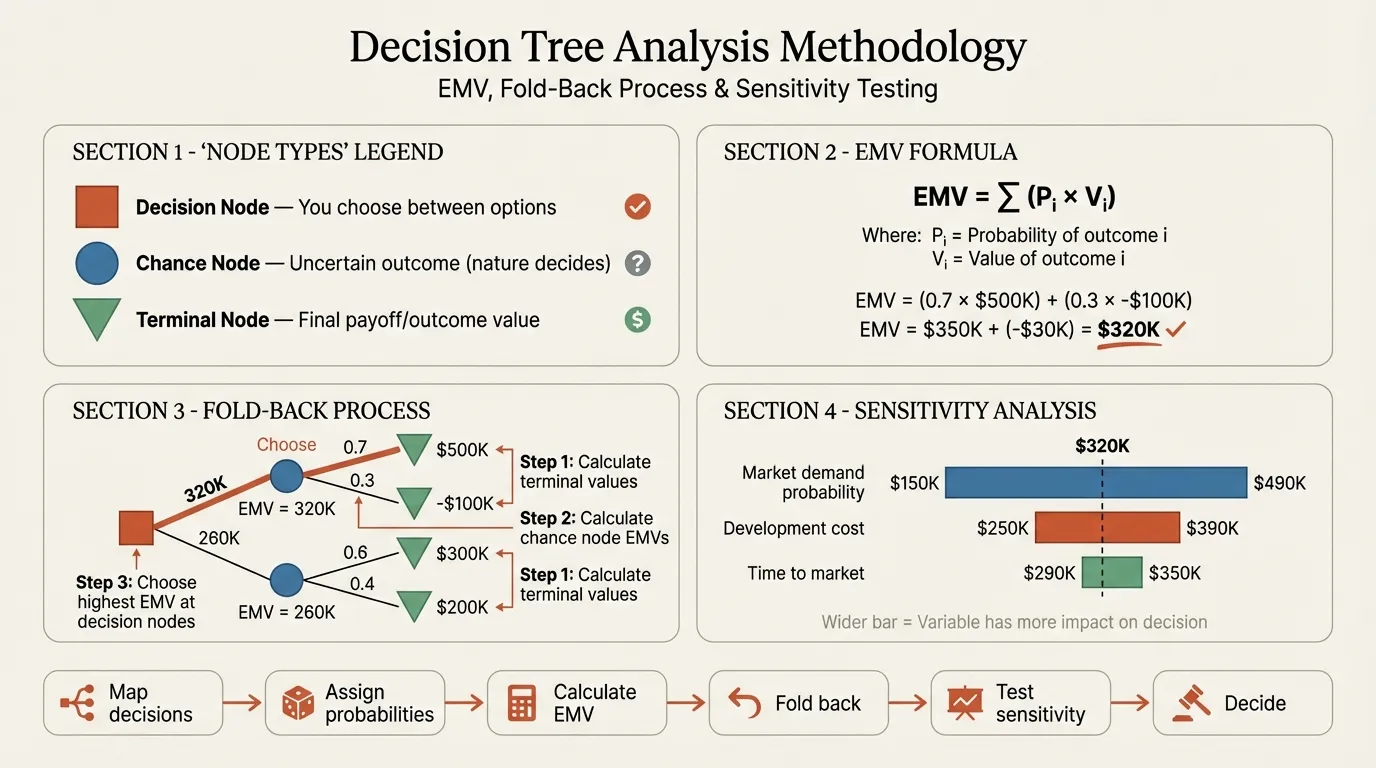

Decision tree analysis translates a complex decision into a mathematical structure with three elements: the choices you control, the uncertainties you face, and the outcomes that result. Every decision tree is built from three node types:

| Node Type | Symbol | Role | You Control It? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision node | Square | A choice point where you select an action | Yes |

| Chance node | Circle | An uncertain event with multiple possible outcomes | No |

| Terminal node | Triangle | The final payoff (revenue, cost, NPV) | Result |

The tree reads left to right. Decision nodes branch into the options available. Each option leads to chance nodes that branch into possible outcomes, with probabilities assigned to each branch. Terminal nodes at the end of every path carry a monetary payoff. The probabilities at every chance node must sum to 1.0.

What makes this analysis rather than just diagramming is the fold-back procedure. You start at the terminal nodes and work backward. At each chance node, you calculate the expected monetary value. At each decision node, you select the branch with the highest EMV. The result is a single recommended path with a quantified expected outcome.

Expected Monetary Value: The Core Calculation#

Expected monetary value is the probability-weighted average of all possible outcomes at a given node. The formula is straightforward:

EMV = (P1 x Payoff1) + (P2 x Payoff2) + ... + (Pn x Payoffn)

Where P represents the probability of each outcome and all probabilities at a chance node sum to 1.0.

Worked Example: Product Launch Decision#

A consumer goods company is deciding whether to launch a new product line. The launch requires a $2M investment. If they do not launch, they keep the $2M and earn $0 incremental revenue.

Decision: Launch ($2M cost) vs. Do Not Launch ($0)

Chance outcomes if launched:

| Outcome | Probability | Gross Revenue | Net Payoff (Revenue - $2M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High demand | 0.30 | $8.0M | +$6.0M |

| Moderate demand | 0.45 | $3.5M | +$1.5M |

| Low demand | 0.25 | $0.8M | -$1.2M |

EMV of Launch:

EMV = (0.30 x $6.0M) + (0.45 x $1.5M) + (0.25 x -$1.2M)

EMV = $1.80M + $0.675M + (-$0.30M) = $2.175M

EMV of Do Not Launch: $0

Recommendation: Launch. The expected monetary value of $2.175M exceeds the do-nothing alternative. The decision is positive even though there is a 25% chance of losing $1.2M, because the probability-weighted upside more than compensates.

This is the fold-back technique in action. You calculate EMV at the chance node, then compare the two branches at the decision node and select the higher value.

The Fold-Back Technique for Multi-Stage Trees#

Most real decisions involve multiple stages. A company might first decide whether to invest in R&D, then -- based on results -- decide whether to commercialize. The fold-back technique handles this by working backward through the tree one stage at a time.

Step 1: Calculate EMV at every terminal chance node (the rightmost layer).

Step 2: At each decision node one level back, select the branch with the highest EMV. Replace that decision node with the selected EMV.

Step 3: Repeat until you reach the root decision node.

The key insight is that each decision node assumes you will make the optimal choice at every future decision point. This is what makes decision tree analysis prescriptive: it does not just model what might happen, it tells you what to do at every stage given rational, value-maximizing behavior.

For a multi-stage example worked through step by step, see the market entry and product launch models in our Decision Tree Examples guide.

Continue reading: Agenda Slide PowerPoint · Flowchart in PowerPoint · Pitch Deck Guide

Free consulting slide templates

SWOT, competitive analysis, KPI dashboards, and more — ready-made PowerPoint templates built to consulting standards.

Value of Perfect Information#

One of the most powerful outputs of decision tree analysis is the expected value of perfect information (EVPI). This tells you the maximum you should pay for any additional data -- a market study, a consultant's forecast, a pilot program -- before making your decision.

EVPI = Expected Value with Perfect Information - Expected Value without Perfect Information

Using our product launch example:

EV without perfect information: $2.175M (the EMV we already calculated)

EV with perfect information: If you knew the outcome in advance, you would launch when demand is high or moderate (earning $6.0M or $1.5M) and not launch when demand is low (earning $0 instead of losing $1.2M).

EV with PI = (0.30 x $6.0M) + (0.45 x $1.5M) + (0.25 x $0) = $1.80M + $0.675M + $0 = $2.475M

EVPI = $2.475M - $2.175M = $0.30M

This means you should pay no more than $300K for a perfect demand forecast. Any market research costing more than that destroys value even if it is 100% accurate. In practice, since no research is perfectly accurate, you would pay considerably less -- but EVPI sets the upper bound on what information is worth.

This concept prevents a common consulting mistake: commissioning expensive research without first calculating whether the information could change the decision.

Sensitivity Analysis in Decision Tree Analysis#

EMV calculations are only as good as the probability estimates behind them. Sensitivity analysis tests how the recommendation changes when you vary key assumptions.

One-way sensitivity analysis: Change one probability or payoff at a time and observe whether the optimal decision flips. In our product launch example, ask: at what probability of low demand does the launch EMV drop to zero?

Setting EMV = 0 and solving:

(0.30 x $6.0M) + ((0.70 - P_low) x $1.5M) + (P_low x -$1.2M) = 0

$1.80M + $1.05M - $1.5M(P_low) - $1.2M(P_low) = 0

$2.85M = $2.7M(P_low)

P_low = 1.056 -- which exceeds 1.0, meaning the launch decision is robust. Even if low demand probability were much higher than 25%, the launch remains positive in expected value terms.

Two-way sensitivity analysis: Vary two parameters simultaneously. For example, change both the probability and the payoff of low demand. This reveals interaction effects that single-variable analysis misses.

Threshold analysis: Identify the exact breakpoint where the decision flips. This is the single most useful output for a steering committee because it converts abstract probabilities into a concrete question: "Do we believe the probability of low demand exceeds X%?"

Sensitivity analysis is where decision tree analysis produces the most practical value in consulting. The recommendation itself is often intuitive. The sensitivity thresholds -- the conditions under which the recommendation reverses -- are what drive productive discussion.

Decision Tree Analysis vs. Other Quantitative Methods#

Decision tree analysis is one of several quantitative approaches to decision-making under uncertainty. Each has distinct strengths depending on the problem structure.

| Method | Best For | Handles Sequential Decisions | Probability Type | Transparency | Complexity Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision tree analysis | 2-4 stage decisions with discrete outcomes | Yes | Discrete | High -- visible logic | 3-4 stages before tree becomes unwieldy |

| Scenario planning | Strategic uncertainty with qualitative factors | No | Narrative, not quantified | High -- story-based | No formal limit, but typically 3-4 scenarios |

| Monte Carlo simulation | Many variables with continuous distributions | Limited | Continuous | Low -- black box output | Handles high complexity well |

| Real options analysis | Staged investments with flexibility to abandon | Yes | Continuous (Black-Scholes) | Medium -- requires financial modeling | Best for capital-intensive sequential decisions |

| Decision matrix | Multi-criteria, single-stage comparisons | No | Not probabilistic | High -- weighted scoring | No uncertainty modeling |

When decision trees are the right choice: The decision involves 2-4 sequential stages, outcomes can be assigned discrete probabilities, payoffs are quantifiable in monetary terms, and you need to communicate the logic transparently to stakeholders. Decision trees are the standard tool in project risk management for exactly these reasons.

When to use something else: If your problem has more than four stages with multiple branches each, the tree becomes unreadable -- use Monte Carlo simulation instead. If you are comparing options against weighted criteria without probabilistic uncertainty, use a decision matrix. If the decision involves qualitative strategic uncertainty that cannot be quantified, scenario planning is more appropriate.

Assessing Probabilities: The Practical Challenge#

The analytical methodology is clean. The hard part is assigning probabilities that are defensible rather than arbitrary. Three approaches work in practice:

Historical frequency. If your company has launched 20 products and 6 achieved high demand, 0.30 is a reasonable base rate. Adjust for how the current situation differs from the historical average.

Expert elicitation. Structure interviews with 3-5 domain experts. Ask for ranges (optimistic, pessimistic, most likely) rather than point estimates. Average the results. The key is asking experts to estimate independently before discussing, which reduces anchoring bias.

Analogous data. Use industry benchmarks or published research. Market entry success rates, M&A integration failure rates, and technology adoption curves all provide defensible starting points.

The critical rule: probabilities at every chance node must sum to 1.0, and every probability should be challengeable with data rather than accepted as a gut estimate. When stakeholders cannot agree on probabilities, that disagreement is itself valuable -- it identifies exactly where the team needs more information before committing.

Common Mistakes in Decision Tree Analysis#

Ignoring the do-nothing option. Every decision tree should include a baseline path where no action is taken. Without it, you cannot determine whether the best option actually adds value over the status quo.

Treating EMV as a guarantee. EMV is a long-run average, not a prediction. A decision with an EMV of $2M might lose $1.2M in a specific instance. For one-time, high-stakes decisions, consider risk profiles and utility curves alongside EMV.

Overcomplicating the tree. If your tree has more than four decision stages or more than three outcomes per chance node, it becomes unreadable and the probability estimates become unreliable. Simplify by aggregating similar outcomes.

Anchoring on the first probability estimate. Teams often anchor on the first number suggested. Use structured elicitation and sensitivity analysis to test whether the recommendation holds across a range of plausible probability estimates.

Building Decision Trees for Presentations#

Decision trees are among the most frequently requested slides in strategy and investment committee presentations. The visual needs to communicate not just the structure but the analytical logic -- probabilities, payoffs, EMV calculations, and the recommended path.

For step-by-step construction guidance, see our How to Make Decision Tree guide. For a pre-built layout with correctly formatted nodes, branches, and calculation tables, use our Decision Tree Template.

Key Takeaways#

- Decision tree analysis converts ambiguous decisions into quantified recommendations using expected monetary value calculations

- The fold-back technique works backward from terminal nodes, selecting the highest EMV at each decision node to determine the optimal path

- EVPI sets an upper bound on what you should pay for additional information before deciding

- Sensitivity analysis identifies the threshold conditions where the recommendation flips -- this is the most valuable output for stakeholder discussions

- Decision trees work best for 2-4 stage sequential decisions with discrete, quantifiable outcomes; use Monte Carlo simulation for higher complexity

- Probability assessment is the hardest step; use historical frequency, expert elicitation, or analogous data rather than gut estimates

For worked examples across five common business scenarios, see our Decision Tree Examples. For a comparison of decision-making frameworks and when to use each, see the Strategic Frameworks Guide.

Build consulting slides in seconds

Describe what you need. AI generates structured, polished slides — charts and visuals included.

Try Free